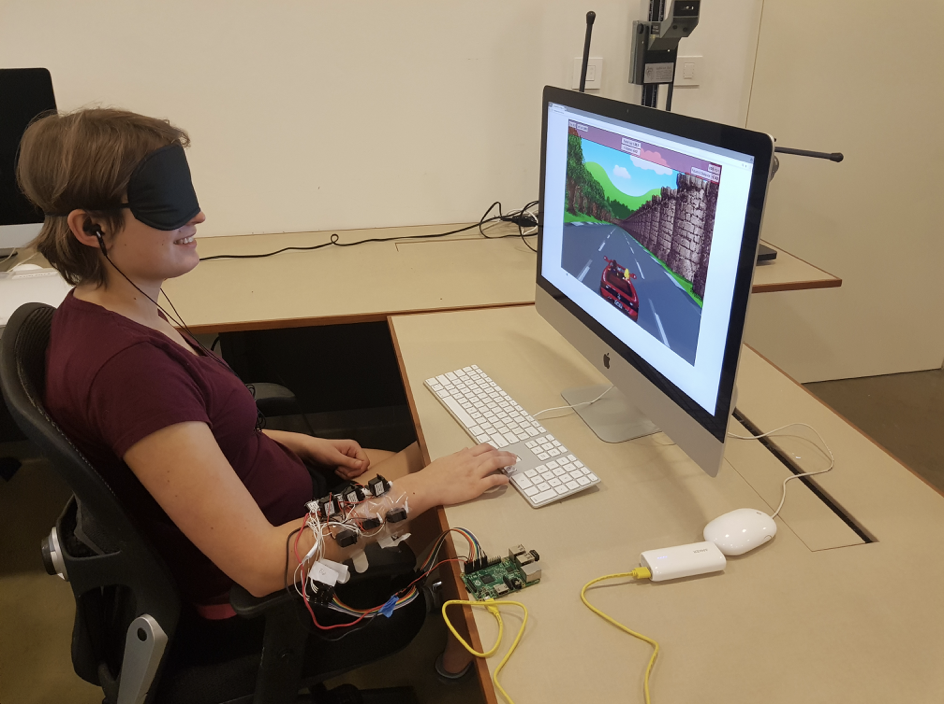

For the quicker readers, the paper (published at the ACM ISS 2017 conference) is here. Below is a quick demo of the project - including pretty girl and cool music - for the ACM ISS 2017 conference:

§Background

In 2003, a ground-breaking paper by a neuroscientist named Paul Bach-y-Rita claimed to have developed a device by which the blind could regain their sight. His solution: the tongue. A series of electrodes attached to the tongue displayed a low resolution image captured by a camera sitting atop the subject's forehead. Through this rudimentary but ground-breaking procedure, subjects both congenitally blind and temporarily blindfolded could learn to distinguish objects and traffic, and catch moving objects with remarkable accuracy with only hours of training time.

In 2016, a bunch of college students attempted something similar and came across his research. We found the one paper, but nothing of substance that succeded it. Surprised as we were, it turned out this wasn't the first time.

In 1969, a Nature paper by the same man reported a mechatronic device which consisted of a chair that had a series of vibrating devices attached to back and cranks by which a camera could be moved by subjects. 400 lbs in total, the bulky device provided a similar experience, albeit with the limitations of the computing technology of its time. The device and its author, by most accounts, slid into obscurity due to a curious inability of the scientific community to accept how plastic the brain really was.

Undaunted, we attempted to build something similar with the technology of our time.

§SensX

Okay - the project has undergone several renamings in preparation for publication - SensX, Servostitutio, GooseBumps - but for the sake of my fingers I'm opting to call it SensX here. I'll save the details of the device and it's operation for the paper, instead describing here the fundamental challenges that we faced, and the surprising discoveries made.

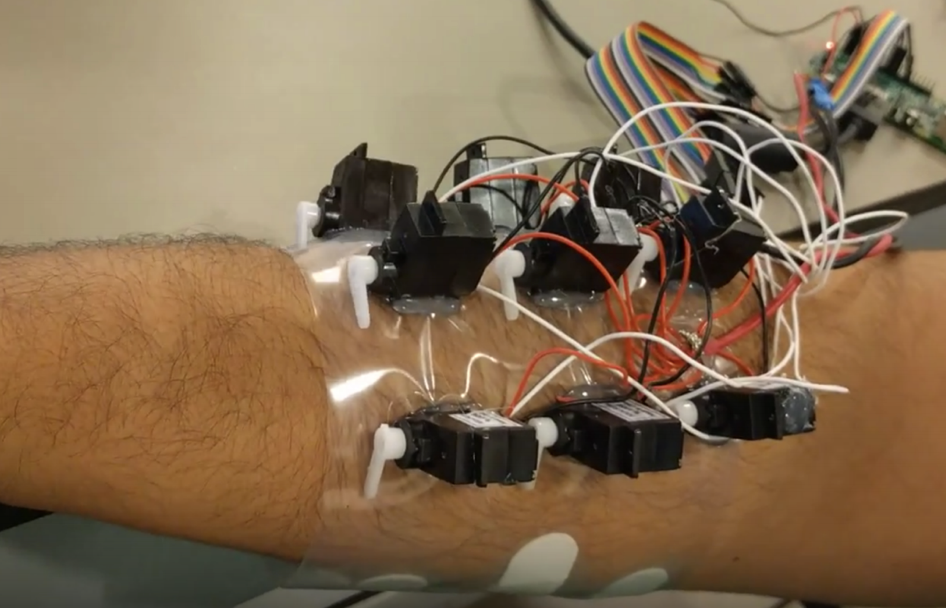

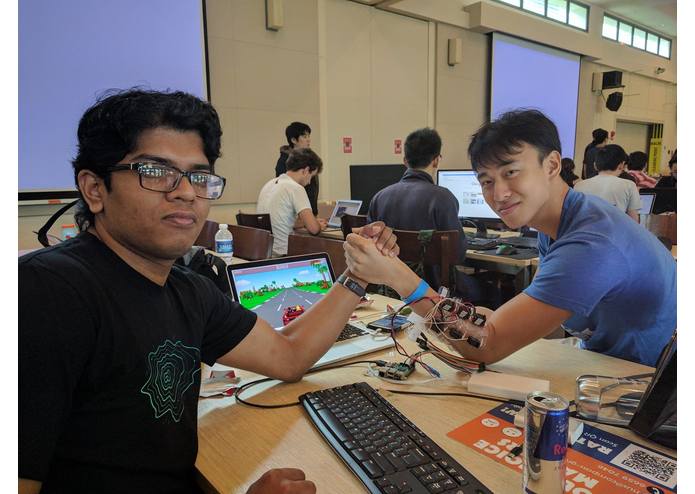

But for a quick recap, the project consisted of a grid of servos attached to the subject's arm, that would lower levers and "poke" the arm of the person. This poking was done over a base frequency, which was varied as certain inputs did. The project was an attempt to find the best way to poke people that they liked (I kid, I kid). It was an attempt to find the most optimal way to transmit information to the brain through a haptic interface such that some neural reconfiguration took place. While this is hard to confirm at a neural level, it was possible - through testing changes in performance and interviewing subjects - to confirm some changes that were brought about due to a change in methodology (see paper for details).

§Construction

The basic material used for construction was determined after much trial and error. The first thing we tried was to have the servos directly poke you, with a simple scaffolding to hold them together. This was done out of concerns that there wouldn't be enough stimulation for the user to know which distinct servos were being used. However, this proved somewhat ineffective as the user was uncomfortable with the feeling of having the servos poking into their arm, while stretching and squishing the skin underneath. They definitely noticed it, but were uncomfortable wearing it for anything longer than a minute. Obviously this was a no go.

The second trial included a large piece of cloth onto which the servos were affixed (add Rocky montage music laid over a lot of sewing here). This proved too stretchy, and unable to maintain a strong relationship between the servos and maintain an aspect ratio. Overall very comfortable, but unlikely to be used long-term especially on areas like the forearm which change in size due to muscle contraction.

After a few more iterations, the best solution was a piece of ESD-resistant bag that one of the ICs came packaged in. This actually turned out doubly effective in preventing static shocks from moving around too much (not planned for but ultimately very happy result). The material was smooth enough not to catch on the user's skin but mould well enough without moving the servos too much or being stretched from usage. This was settled on for the final solution, with the servos laid on top of the piece of plastic. Some velcro was used to affix both sides of the device to each other.

§Control

The control circuit involved using a Raspberry Pi (nomohead to the rescue), and a simple wiringPi script that allowed for controlling the servos. Unfortunately, we ran into a fair amount of problems here.

First, the Pi doesn't do hardware PWM for more than a few channels, and we had over 9 servos to be independently controlled. We didn't have time to make use of a dedicated control circuit (which I highly recommend if you're building one - this looks like a good buy), and ended up using software PWM along with our own homebrewed event-driven control library that could receive signals from the control game and pass it to the servos (code is here, but it's rather simple and very hackathon oriented).

For another, the PWM signal from the Pi - regardless of whether it was hardware or software, drifts a fair bit on both frequency and duty cycle, which kept the servos jittering and producing their own vibrations even when they weren't moving. This led to phantom effects on the user (like how it feels when your phone vibrates in your pocket but isn't really), throwing off the results. This was solved somewhat with a capacitor across the terminals, and by slowing down the overall speed of the event loop, which was still well within our own requirements.

§Results

Finally, the results were quite interesting. The paper has more details regarding what we changed, but when moving between methods of processing the input and relaying it to the user there was two primary clusters that performed differently. The first was when the users reported that they had to memorise the combinations of input for certain actions and what they meant, and the second was when the user began to 'feel' the input and simply adjusted accordingly. As predicted, the second group performed much better than the first, leading us to suspect that there was some neural reconfiguration at play. It was possible that - much like the paper originally discussed - the changes enables the brain to recognise the new and unfamiliar input as something that could be made sense of outside of the conscious mind.

Overall, quite a fun experiment. The project was a hit at the hackathon, and I'm hoping to present it in Brighton this month, will post any updates here.

Not a newsletter