There is a problem that has been troubling me for a number of years now. The rise of crypto around the world has led to it being hailed as the replacement for centralized banking systems, a new international coin, and monikers far too numerous to mention. And while the community is well aware of and hard at work to solve the scaling, privacy and hype issues surrounding crypto, there is perhaps a separate economic problem that lies at the heart of most currencies. This is the problem of dead money.

§How it exists

Before we begin, let's consider the basic nature of a currency. This is somewhat contentious, so consider the following evaluation a launchpad for the argument thereafter. I'm forced to make copious assumptions to get to the heart of the matter in a brief way, but rest assured they are not conceded.

To begin with, let's consider traditional currency markets. I have been trying to find past discourses on this particular issue, but having come up short I am forced to revert to classical economics for analogies.

A unit of currency is traditionally a store of value, often backed by a central authority through a one-to-one backing or a promisory note. Most currencies of the world today are the former rather than the latter, and this is a discussion we will get into later. A promise of some stable value then provides utility to the units of that currency, as they are often far easier to exchange and transport than physical items of the same value. If you've read the previous article on investing, we can consider the currency of a nation the "base market" of most exchanges happening in that country. All exchanges are mediated, or measured against the base pair to provide an accurate measure of their true worth.

A number of other attributes are required of a currency, such as the ability to make and prove transactions, divisibility of units and so on. We'll sidestep this discussion for a moment, as this was been well explored in the world of crypto. Moving on, let's consider the introduction of one of the largest and most controversial inventions in the financial world: fractional banking.

Sal Khan does a good job of explaining fractional reserve banking here, but simply put it is a way that debt - or borrowing against the future - can help economic growth. If you store $100 in the banking system, this money can then be lent out to someone that can add value to the market. This is how most of the world's banking systems function. At any given time, banks do not have all of the collateral they owe their users. That money is reinvested in the economy to stimulate growth. This has played a huge part in the economic booms of our lifetime, but it is not without its issues. The same leverage also leads to boom and bust cycles, and is also in large part responsible for the recessions of our lifetime.

On the outset the whole concept can seem far-fetched. Debt at the individual level - in our personal lives - is rarely a good thing. However, at the industrial and societal level, debt is what allows us to grow faster than the standard supply of capital would let us. When building a farm, it is sustainable and often advantageous to be able to pay your workforce from borrowed future returns on it. At an institutional level, lack of leverage (or debt) is not a good thing. A good many things can be built on the promise of value, and this is what has pioneered the explosive growth of the world economy over the past century. It does sometimes get away from us, but it is the ability to have otherwise stationary investments (an unbelievably large portion of the world's wealth) work for us that has brought about the world we live in. Forbes did a small piece on it a while ago, but to cut a far longer conversation short, a healthy amount of debt is a good thing. A country or institution not in any amount of debt is often curtailing its own growth.

§The Problem

I'm worried there's nothing like it in the world of crypto. Before we get into it, I should mention that I'm not dismissing the notion of utility tokens, where the capital is used by companies and developers to build useful products. Despite the looming and ever growing size of the ICO market, there are good companies and people out there that are building products using the capital raised. This is decidedly not dead money. Not yet.

ICOs have two hurdles from truly mobilizing the capital involved in crypto markets. One, the utility promised is often quite small compared to the investment being courted, and the investments moving into ICOs are often a very small portion of the total liquidity of the crypto currency market that lies beneath them.

Two, the utility value promised by ICOs is often speculative, and the utility value is always on a steady decline. For example, let's consider a token that is used to express satisfaction at content found on the internet, and subsequently encourage better quality. The developers of the token need capital: after all, they have a serious amount of work to do in developing the protocol, testing the code against exploits and making sure it achieves widespread success. The capital raise commonly goes one of two ways: One, the developers keep 20% of the tokens for themselves and release the rest as free access or to be mined. As users assign their value to the tokens based on utility and speculation, the developers can sell their percentage for compensation. Two, there is a token sale where the developers hold some form of auction where they receive some other currency (often BTC or ETH) in return for their tokens.

In either situation, let's consider the amount of capital invested into the project as leverage - a somewhat untenable proposition, but let's stick with it. While the users can continue using the tokens for their value, the developers can use the capital to build the platform and additional features. However, let's move ahead a few months (or years). The platform has been built and is operational, and the users and developers are happy. There are a few bug fixes and small features on the horizon, but the core development team has left to pursue newer projects and the product development team is much smaller - in size and/or contribution - than at its biggest. This is quite common, and for a simple reason - it takes far less effort to manage a completed project than it is to create a stable one from scratch.

This is where the ICO model completely deviates from any leveraged model. In the banking scenario, this is the point where the investors either exit or recoup their original debt with interest, moving on to the next investment. However, in the case of the ICO, the true investors are the users, and the capital spent begins to slowly - perhaps asymptotically given a long-lived project (and efficient markets, which crypto has demonstrated itself not to be) - approach zero in it's contribution.

A large portion of the wealth in cryptocurrencies is simply stationary. In the old-fashined world of paper currencies, this is akin to burying a large box of cash in your backyard and waiting for inflation to set in. Few people other than drug dealers, money launderers and large tech companies (Palantir and Apple) are engaged in this business (I'm kidding about the last one - it's useful to have some liquid cash on hand, and companies do this when expecting the apocalypse). Compare this to the developed world where it's impossible to run a business without some form of leverage, and we see the difference.

§Solutions

Just to be clear, I'm not advocating that we inflate the entire currency supply by 1000% and pass the extra coins to JPMorgan Chase for investing. There are dangers involved in fractional currencies, and issues related with over-leveraged systems. However, a currency without any leverage is ultimately a deceased store of value.

Another advantage of leverage-friendly systems is that the concept of complete escrow can be (at least partially) done away with. A number of smart contract systems if not all employ a complete escrow of third party funds in order to perform a service. While this ensures complete trust, it does so at a cost. Consider the example of a competitive betting market with multiple bookies and a large pool of players. In order to make sure that bets are always fulfilled, a smart contract holds the funds in escrow and releases them when the results are confirmed by one or more trusted oracles. While this ensures that all players can be assured of their winnings, consider the alternative. Let's go to the extreme other end and design a system where the bookies hold all of the money from the bets and are free to do as they please as long as it is in their possession. A simple strategy to maximise profits would be to loan the funds out for the term that they're expected to be held in order to earn interest. In a competitive scenario, the players that do this will have a much lower risk exposure and better profits than their competitors, and will be forced to pass this to the consumer to create a more attractive product. Everyone benefits.

Unless someone pulls a Mt.Gox. Complete leverage is rarely ever good, and if anything the argument is for a healthy amount of leverage in a system. This is incredibly complicated in a trustless system, as the concept of pure risk and debt are very hard to enforce in anonymity. However, if there is a point to this rant, it is that it might be worth it to try.

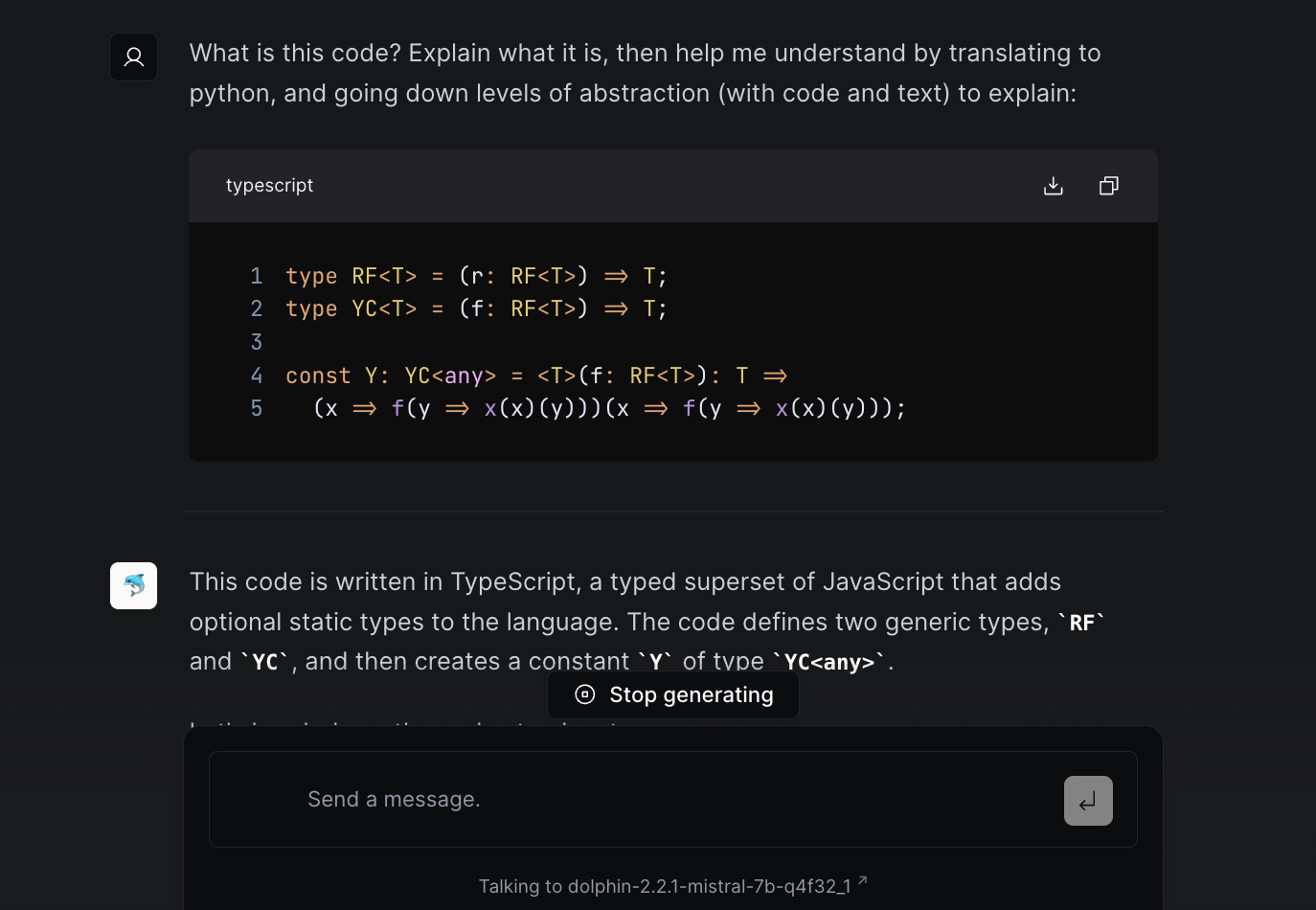

Now none of this is to say I've got a solution to the problem. The only point to this post is in exploring something that's been on my mind for a while, and hopefully drawing attention to a big problem I don't see being talked about often. If you're interested to read more, Vitalik's blog is a good place to start - he's a significantly better writer, economist and coder than me.

Don Delillo's Cosmopolis has a beautiful scene where the characters discuss a world where the rat becomes the unit of currency. "Russian stockpiling of dead white rats called global health menace", or something like it. Currency uninvested is dead, and most of crypto seems pretty lifeless to me.

Not a newsletter