Let's go down and confuse them! We'll make them speak different languages, and they won't be able to understand each other.[1]

The early internet had a problem.

ARPANET and TCP/IP let us send packets between computers, but connecting networks of machines to each other caused a never-ending cascade of packets flooding the network, bringing everything to a screeching halt. Termed ‘congestion collapse’, it seemed an intractable problem at the time.

In 1988, Van Jacobson devised a brilliant solution to this problem that made the modern internet - a collection of billions of smaller networks, like the one you have at home - possible. All of those networks could be complex and varied in their own ways, and yet find a way to be part of a single, large substrate of extended knowledge.

Humans are complex and varied. We speak similar but different languages, generate similar but different data - and this is a problem for computers. Even the same human will find it hard to reproduce things exactly. We think in the spirit of things, and computers measure letter-first.

Once you see it, you’ll notice that a large share of humanity works on transforming information from one shape to another. Our governments, companies, and people spend untold amounts of money and time simply reformatting data.

This is going to be one of the problems that define this decade. Through no fault of our own but our very nature (and the occasional attempt at making walled gardens), the information we’ve been saving for decades now is in silos made of trillions of schemas. (A schema is just a fun way to say structure or shape).

As a younger man I looked at solving human problems in shipping and insurance, yet my time (which is now the better part of a decade) was mostly spent cleaning and unifying data siloes. This was the problem to be solved before there was any foundation to solve other problems.

Humans have - until now - been alone in our world as the only universal connector. We are beings capable of learning and understanding completely new schemas and unifying them through experience. It takes general intelligence to infer relationships, unify fuzzy similarities and see meaning across formats.

Since 2022, we aren’t the only Mentats on this planet. We have company - we have help.

§Why is this hard?

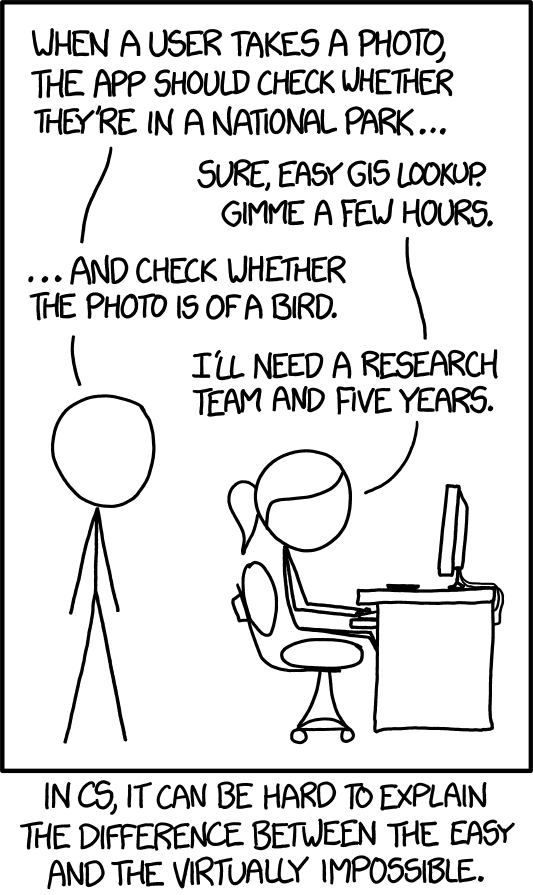

This is one of those problems - like catching a ball or walking seven steps - that seems excruciatingly easy, but turns out it’s only easy if you have six million years of evolution behind you.

Take the simple problem of outlier detection. The first task of any processing system is creating a description of the shape of incoming data. Once you have it, you need to look at the things that don’t fit - are they true outliers, or did you get your shapes wrong?

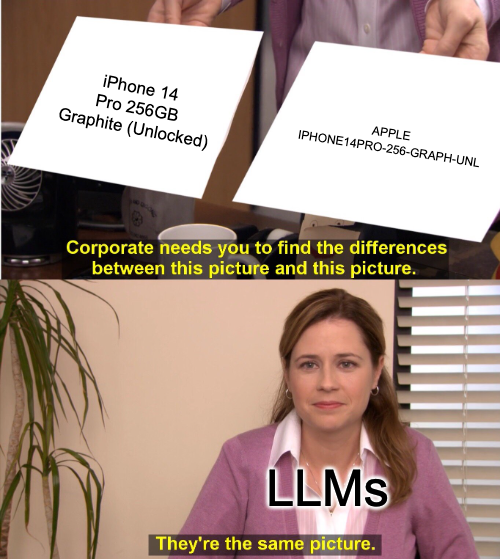

Humans can look at ‘312312’ and tell you that it doesn’t belong in a date column, while ‘12-Jan’ does (or ‘Stardate 41153.7’). So can LLMs.

§So why is this still hard?

The advent of LLMs has made previously hard things easy. They’ve opened us up to imagining that harder things will get easy as well - but that’s not always the case.

Language models are good at extraction. Give them some information and a schema, and they’ll pull things out. You do this every time you paste something into ChatGPT and ask for a list of things from that information.

Yet they can only handle so much. No matter how much more they can read, we continue making more. The more you give them, the worse they get at thinking. Not unlike us.

Passing information through models is an unscalable approach - and the first path we shouldn’t walk down.

Don't embeddings help, I hear you say? Modern vector search systems have an uncanny ability to connect semantic meaning, to search across the boundaries of tables and sentence structure.

However, vector approaches remove the most important thing about information - context. Chunking and embedding vaporises precious structure and context (which table was this in? Who made it? What else refers to it?). Search performance with an unstructured base of vectors degrades with an increasing search space. This also makes them horrible at numbers, exhaustive searches, and agentic retrieval.

It also loses us one of the most important properties of modern AI systems by turning search back into a black box.

Unstructured pipelines are unfit for already structured data (which is almost all data), and limited by their ability to connect new information through context.

§Artificial Schema-dreamers

Outside of school, modern human beings rarely memorise and repeat information to transform it. The same way we don’t bring our fists down on nails to join wood, we operate tools that are far better at each task. Over the last 50 years, we’ve built wonderful tooling that can query, index, transform and serve information on incredibly small machines.

LLMs are wonderful at handling tools - and they’re only getting better. If we can build the right ways to think of information, arm the AIs with the right principles and a lot of good engineering, we can solve the problem - in the general sense.

We can build systems that preserve information as they operate on it. Imagine being able to throw information into a bag that is neatly organized by thousands of agents (artificial schema dreamers, as Claude put it). We can have a unified substrate that can deliver high-throughput realtime information to support decision-making, business intelligence, generated UIs, and all the things we haven’t thought of yet.

So how do we do it? The rest of this piece is split evenly between our technical approach and the underpinning political philosophy of building a company around it. If I can manage it, we’ll close with something poignant.

§Focusing on the beginning

Three years ago, something I wrote about cleaning a room struck a chord with a large number of people. The problem I identified then, which became the underpinning concept of Southbridge, was structure. All information is naturally structured. Nature is negentropic, as are humans - we just decide when we want to enforce our structures.

The lazy way, both for humans and computers, is to do it at query time. If you want to find something, clean your room and look for it. If you want to retrieve something in a dataset, organize the dataset in relation to your query.

Yet this approach doesn’t scale. Queries are varied, and all of them demand immediate answers. Your users are exactly like you when you scramble to find your keys. Query-time is the time when you don’t have any time at all. It’s expensive, unscalable and under a lot of constraints.

Any dataset, if sufficiently large, will contain enough implied context for retrieval and transformation. This information is often lost right at import, often because the right tools don’t exist to capture and infer it at the source.

“The currency for transactions is in the desc field - just look at the dataset!”

Use almost any AI system today and you quickly end up having to tell the system to "look at the dataset." What that really means is that the information needed to solve the problem could be inferred from the data, even though it's not explicitly present in the text.

Think about a table of country codes, names, and postal codes. What you actually have in the dataset is exactly that – just codes and text. But there are multiple levels of understanding we can build.

-

Level one is the data itself. Are the postal codes just numbers? How are the names organized? This is information you’d need to retrieve simple things from the data. If you want to search for a name, you need to know that names in this dataset look like ‘John Smith’ and not ‘Smith, John’. Fuzzy/semantic search can help you here, but only so far - and not with numbers and dates.

-

Level two is about the dataset. This is a database of addresses. Maybe this is a dataset of addresses in California. You’ll need to know this if you want to find this specific dataset in a large database of hundreds of datasets. “Where did we put the addresses again?”

-

Level three consists of cross-dataset implications. Maybe the country codes are in a company-specific format that links to a countries table somewhere. Maybe the addresses are only partial, and you need to find the actual invoices in a folder to get the full thing. We’re quickly approaching problems that humans can grok at a glance, but we’re still figuring out how to give that ‘glance’ capability to our artificial minds.

Lots of levels exist above this one, and unstructured pipelines throw away these valuable layers of meta-information, somehow expecting to retrieve them at query time. The challenge is not just inferring them, but storing them in a way that allows for flexible transport and reindexing as needed. You want to find your banana without retrieving the gorilla holding the banana and the entire jungle.

§Building a true Southbridge

Once upon a time - when I was busy trying to get my first computer to boot (it never did) - a little chip sat south of the CPU that connected it to the outside world. This little chip (and its successors, who were more boringly named - except for AMD, who called it the fusion controller hub) was responsible for presenting a unified interface to the CPU of everything that happened. Different devices - connected randomly, erroring out occasionally, being yanked out of their ports well before their time - needed to be managed with grace and poise.

How do we do the same thing with modern information sets? Here’s how we break it down:

- Import at the Edges: First, we need to figure out everything that happens at the far outer edges of import. How can we pull information into some broad structure while preserving as much of the original information as possible? This means handling XLSX files, PDFs, and all sorts of formats. There are wonderful companies already doing some of this work we partner with, but none attempting unification at scale.

- Understanding & Enrichment: Once we have the data, we start understanding its structure and enriching it. Can we break it into component parts? Can we build highly descriptive schemas that accurately shape around this data? Can we capture the characteristics and underlying rules of the dataset? The goal is to keep building and enriching as we go.

- Unification Through Fingerprinting: After enrichment, we start unifying or splitting the data based on similarity—think of it like Shazam for data structures. If we take a nested JSON approach, we need to find similarly shaped parts and unify them while keeping everything connected.

- Relational Transform: Finally, we flatten the data while maintaining a flexible grab-bag for future ingest. At this point, we have an end-to-end pipeline that can serve as the backbone for building retrieval systems or as master data for a company.

But these are just the basics. The real engineering challenges come with scale:

- How do we handle schemas that change halfway through import?

- Can we process unstructured blobs and enable multi-modal ingest and retrieval?

- How do we implement stream processing for large, moving datasets?

- What's the right unified data structure that's extensible without becoming an unwieldy ontology?

- How do we backpropagate true signals of success or failure (from the end user) all the way back to step 1?

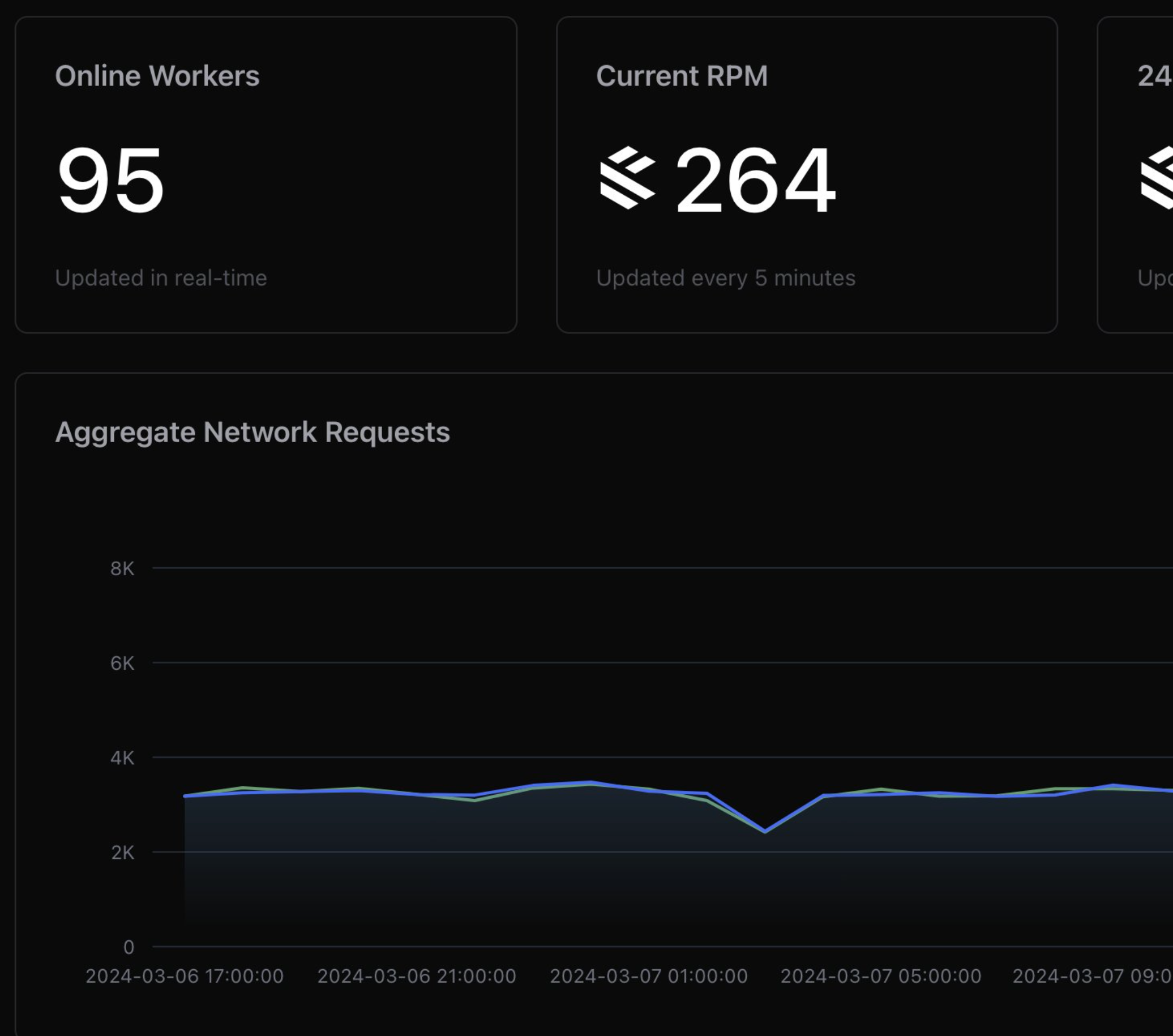

You’ll soon hear from us on our solutions (which are already importing information using small local models at Gigabits/s) and how they work, or as we open-source the things we build. More on that shortly.

§Building for ourselves and others

I’ve always felt that companies that can use their own products live a different life. Every update is more meaningful. Bugs are treated differently. Ideation is easier. We want to use the things we build - no matter where they end up. We want them to have a chance at being useful to us as individuals, and as a company.

We also live at a point in history where change seems to be the norm. Perhaps it’s the industry, the approaching singularity, or the fact that I just turned 30 - but things seem faster now. Like a flooding forest, previously tall branches now have low hanging fruit - if you can swim. Previously difficult things are now so easy they don’t even need people, much less a company.

It’s also understandable - the magnitude of the last two years often escapes me. Since blowing past the Turing test, for the first time in human history, we have minds of similar general intelligence to look inside of. The next decade will bring paradigm-shifting insights into how artificial intelligences perceive and process information. When new capabilities emerge – whether in models, methods, techniques, or structures - an ability to ditch old methods and kick up to the new waterline will mean all the difference.

This is why the core development approach we’re starting with involves micropackages - locally executable, easily connected packages that are useful in their own right, both as part of a larger codebase, and as daily-use tools. They help us think of the interface layers better, and switch to new approaches quickly.

Tip20, offmute, eloranker and diagen are already part of our daily workflows and our codebases.

We also intend to open-source our component systems. We believe its the right thing to do, when the exchange of value is lopsided for so much of what we build. The AI industry today has so many repeated and rebuilt pieces inside silos - from templating to model adapters - that can’t benefit from stability that use at scale brings. Most of what we build today will create and contribute more value to all of us than we lose in a competitive landscape. Value in finding the right people to build with, understanding new use-cases we haven’t thought of, and trust and credibility that we understand the problems we’re trying to solve. Yes, there will be components so business-specific that open-sourcing them will only benefit competitors - but these are the exception, not the rule.

§The future we see

The systems of tomorrow are going to be radically different. Today, companies might spend five to six years training a human to understand their data before trusting them with significant decisions. But imagine scalable, multi-agent AI systems spinning up hundreds of copies of themselves, each working with different datasets, making decisions and communicating amongst themselves thousands of times per second. We no longer have the luxury of that human timescale.

We believe the systems of the future won’t care what format information is buried in. New networks will emerge that abstract things into a unified substrate, much like the Intergalactic Network (which became ARPANET, and then the Internet), making it easier for intelligences of the future to think better.

Any expression of intelligence is a transformation of data. We just want to make it easier. With a Southbridge.

Not a newsletter