This is part 2 of a series on improving retrieval-augmented-generation systems. Part 1 covers the basics of such systems, key concerns such as question complexity, and the need for new solutions.

In this part, we'll cover the basics of multi-turn retrieval - what it is, why it's needed, and how to implement it. If you were interested in how WalkingRAG works, this article should leave you with a working, implementable understanding of how to build a similar system.

§The Problem

Almost all RAG systems today work 'single-shot' - for a given question, they retrieve information, trim and modify, and use an LLM to generate an answer. Prima facie this seems okay - until you consider how humans answer questions today.

Let's presume that you're an above GPT-4 level intelligence. How often have you been able to solve problems with a single round of retrieval? In most cases, your first round of Google searches, combined with any residual information you have, gets you closer to finding the answer - rarely do you have everything you need for a comprehensive, correct response from the first round alone. We need a method for the central intelligence - whether that's you or an LLM - to ask for more information, contextual to the retrieval that has already taken place.

Moreover, expecting single-shot RAG to hit higher and higher benchmarks is placing an impossible requirement of intelligence purely on the Retrieval system. In most cases this is an unfortunate embedding model that's trained for semantic understanding, or something even simpler. Trying to push single-shot retrieval to human-level is an easy path to larger and larger vector databases, longer context embeddings, and complex embedding transformations where you can burn large amounts of money and dev time without much benefit.

The solution that worked for us with WalkingRAG is to find a way for the LLM - the largest and most intelligent brain in a RAG pipeline - to ask for more information, and to use this information for multiple rounds of retrieval.

To have effective multi-shot retrieval, we need three things:

-

We need to extract partial information from retrieved pieces of source data, so we can learn as we go.

-

We need to find new places to look, informed by the source data as well as the question.

-

We need to retrieve information from those specific places.

If we can successfully connect all three, we can do multi-turn retrieval.

§1. Fact Extraction

We'll be using GPTs and Huggingface Assistants as demonstrations of individual concepts. The prompts will be provided, but there's something about an interactive prompt you can poke at.

The prompts used are intentionally stripped down to be illustrative - I apologize in advance for any brittleness in the outputs!

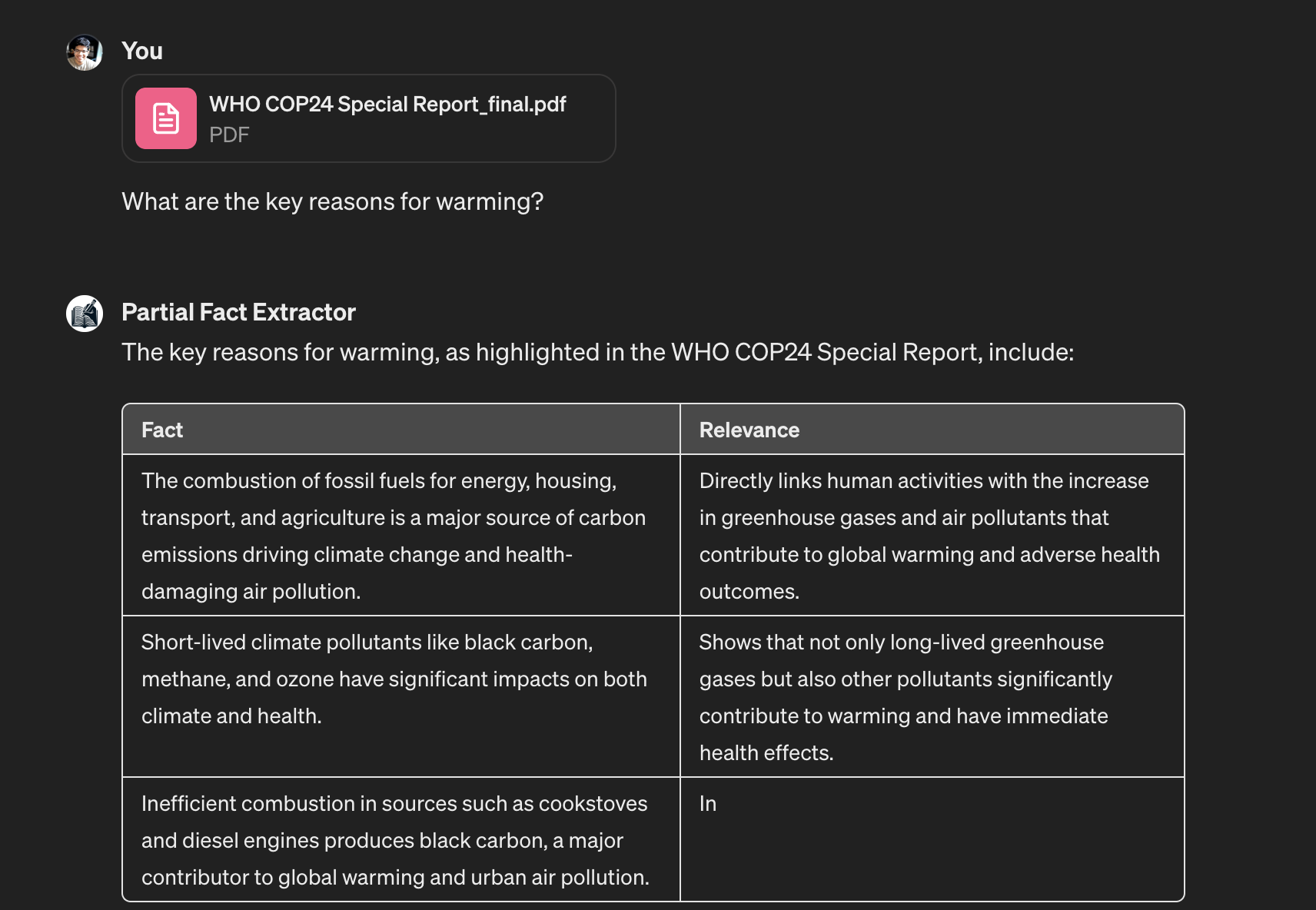

Here's a GPT that demonstrates fact extraction. Give it some document or text, and ask a question. The COP24 report is an easy public source you can use as a large document for testing. Let's load the document and ask a mildly complex question:

If you remember Part 1, you'll know what's happening under the hood: OpenAI's RAG system retrieves a few relevant chunks from the document we've uploaded, sorted by embedding similarity to our question, and passes these to the LLM to use for an answer.

However, in this case, we're asking the LLM to extract individual facts from the chunks provided instead of an answer, as well as a description of why this fact is relevant to an eventual answer. We're adding an extra step - almost like a chain of thought - that will help us start listing out the information we need. Think of going to a library, and keeping a notebook of useful information as you pore over books of information.

We internally call these Partial Facts - information extracted from the document that is at least loosely relevant to the question being asked. Here's the prompt we use:

Make a markdown table of relevant facts, following this typespec for the columns:

"""

fact: string; // Provide information directly relevant to the question - either supplementary data, facts, or where the answer might be located, like pages and sections. Add definitions and other context from the page into the fact, so it's self-explanatory.

relevance: string; // How is this fact relevant to the answer?

"""

Note that the output is in Markdown here for readability - inside WalkingRAG we extract this out as streaming JSON.

Here's an example of facts as they stream out of WalkingRAG:

§2. Finding new threads

Once we have partial facts, we want to know what they tell us about new places to look for additional information.

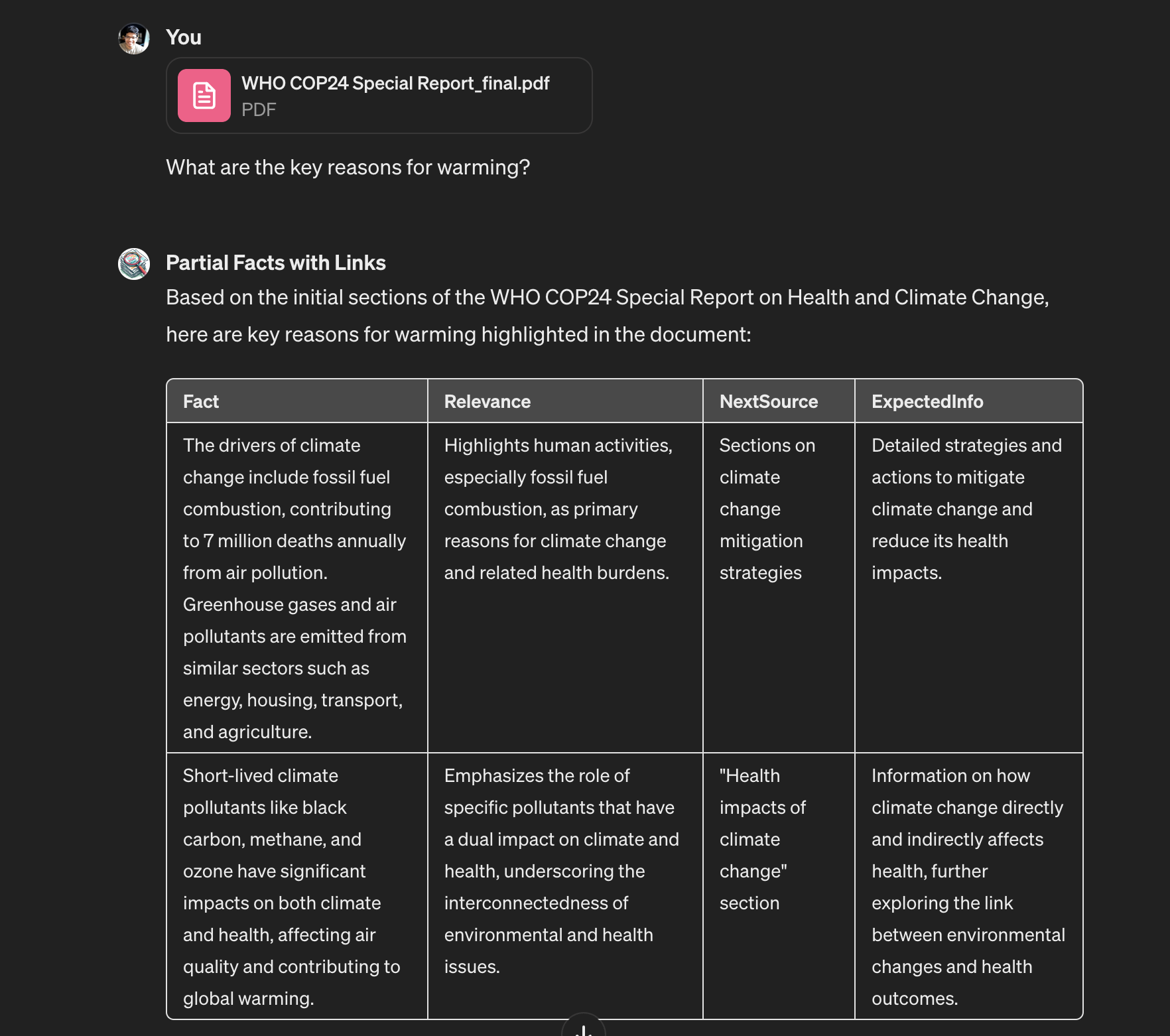

Try the same document and question with this GPT. Let's ask the same question, with the same document:

What it's doing here is extracting references from the chunks that were retrieved. In most cases, complex documents will tell you outright where to look for more information - in footnotes, references, or by naming topics. It's often trivial to extract them, without much additional cost - since you're already extracting facts.

All we've had to do is to expand our typespec, just a little:

fact: string; // Provide information directly relevant to the question (or where to find more information in the text) - either supplementary data, facts, or where the answer might be located, like pages and sections. Add definitions and other context from the page into the fact, so it's self-explanatory.

relevance: string; // How is this fact relevant to the answer?

nextSource: string; // a page number, a section name, or other descriptors of where to look for more information.

expectedInfo: string; // What information do you expect to find there?

§3. Connecting the threads

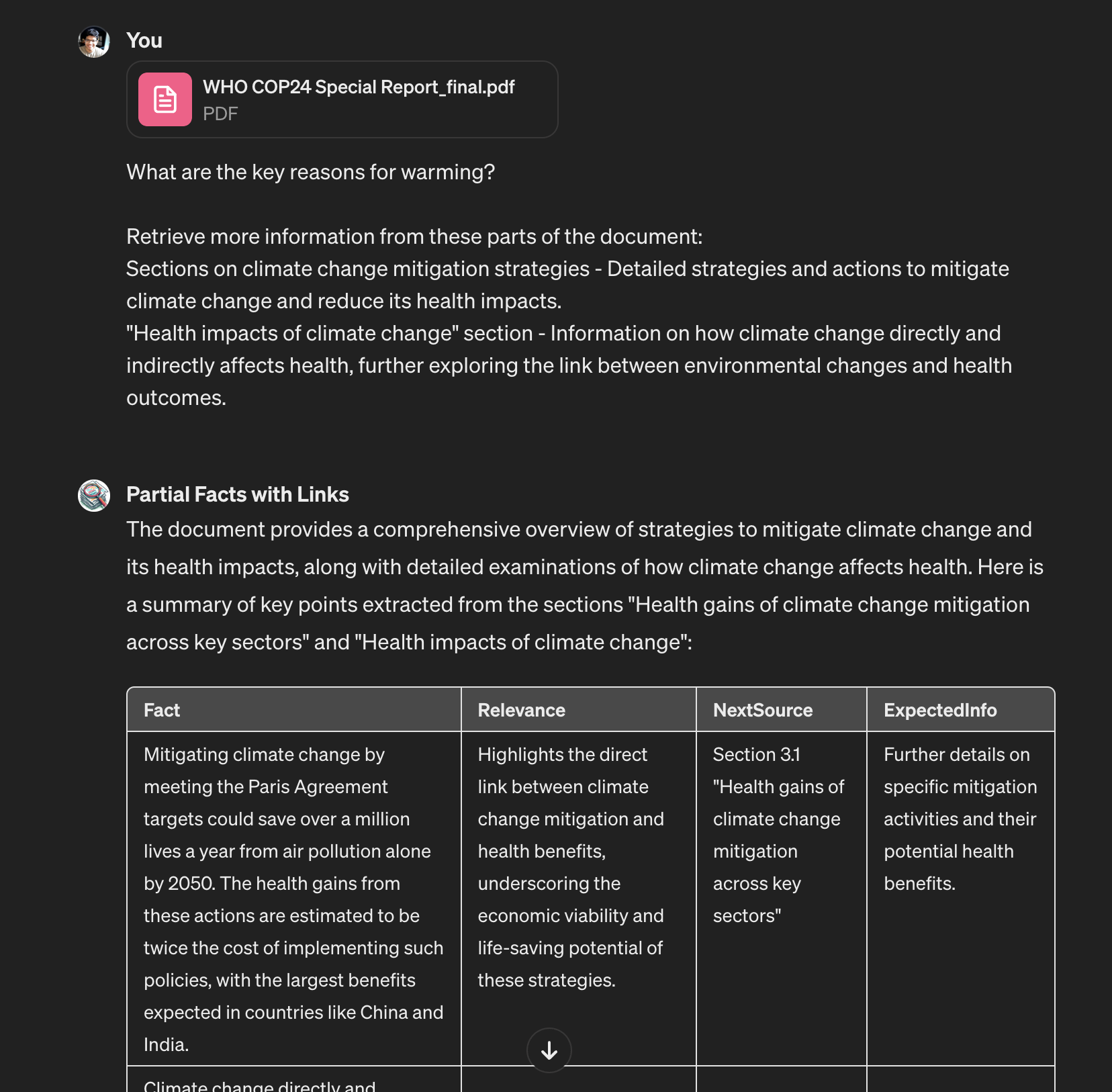

Once we have these references - in our case, we're looking for 'Sections on climate change mitigation strategies' and 'health impacts of climate change' - we need a way to retrieve new information from the document specific to these descriptors.

This is where embeddings can be quite useful. We can embed the descriptors, and use them to search the document for new chunks of information that were missed by the previous round of retrieval.

It's hard to demonstrate this with a GPT, but try pasting the descriptors right back into the conversation and asking for more facts - chances are you'll find newer, more relevant chunks and information.

Inside WalkingRAG, we embed the nextSource and expectedInfo descriptors, and it works quite well. The semantic distance we're trying to bridge is a lot smaller - often the document will refer to the same thing the same way, and we can filter our results to make sure we retrieve newer pieces from the dataset.

Now all we have to do is repeat the cycle, this time from the embedded descriptors instead of the question. We keep the facts we extract - and two very desirable properties emerge: increased entropy and intermediate outputs.

§Entropy

Entropy is a useful term to describe the amount of information contained in a sentence. In human terms, we can call this context. Every time you've asked 'What do you mean?' in response to a question, you were likely asking for more context - or entropy.

The role of entropy in semantic-search based systems cannot be understated. Most human questions to AI systems have a massive amount of implied context that is hard to infer from the question alone. Humans like to be terse - especially when they type. This is fine with other humans, who can infer a massive amount of context from the physical, professional and historical states they share with the person asking them to do something.

For an automated system, there is often painfully little information in the questions you get. For example, 'Where is the big screwup?' embeds the same, regardless of whether the target document in question is Romeo+Juliet or the Lyft Earnings call transcript.

The process of walking helps us enrich the original question with contextual entropy from the dataset to further guide the eventual answer.

§Intermediates

You'll notice that we generate quite a bunch of intermediate outputs in our process. With a single cycle, we have extracted facts, relevance, expected next source descriptors and potential new information.

This is a wonderful thing - even without any additional processing, there is already a lot that we can now do:

-

We can provide immediate feedback to the user about what goes on behind the scenes. This makes it easier for users to trust the system, verify outputs, and provide more feedback when the final result isn't up to spec. In a more complex system, users can interrupt cycles, modify outputs or questions, and return control to the system to steer it in a new direction.

-

The intermediates label and classify the document as more questions are asked - giving us a kind of long-term memory. We have extracted facts, which are a good source of information to be re-embedded and searched instead of the source document. We also know the causal paths we take through the document - where the false starts are, and where cycles usually end.

-

We're also building a knowledge graph of the document, with the cost-effective method of doing it at query time. In WalkingRAG we also build one at ingest - this is something we can cover at a later time, as a way to tradeoff cost for better accuracy.

§Conclusion

The information we record as humans - in PDFs, text messages, excel sheets or books - is deeply interlinked, as much as we are. Nothing means much in isolation - and the first look at something usually isn't enough to get the full picture.

Cycles - or walkingRAG, or agents, call it what we want - are a way to improve the complexity of questions that modern retrieval systems can handle. Some things I've left out for clarity - how we build the graph at ingest, transformations on input data (to be covered in a later article), and how cycle terminations are implemented.

In the next part we'll cover how structure in your dataset is an untapped resource, and how to make use of it.

Not a newsletter