For the longest time, it's been a fun exercise for me to look at something and imagine how it got there. Back before I had a smartphone in the loo, it was an adventure of the mind to look at the tiles, the pipes and the things I had around and wonder what lives they'd led before they intersected with me.

It's a habit I've maintained, and one that I've noticed has become increasingly complex and hard to do. The things I now see are impossible to trace, each of them a complex maze of parts that were conceptualized in one place, designed in another, manufactured, assembled and packaged in possibly different places. Having spent my earliest years in a village in India, the difference is startling. I wonder what it means for us as a people, and what it means for the things we build.

Risking overgeneralization, this seems to apply to things across disciplines, across shape and form. I see this with the people I know, the things I own, the software I use, and perhaps even my world at large. The thread of history that can be unraveled seems to be getting shorter and shorter.

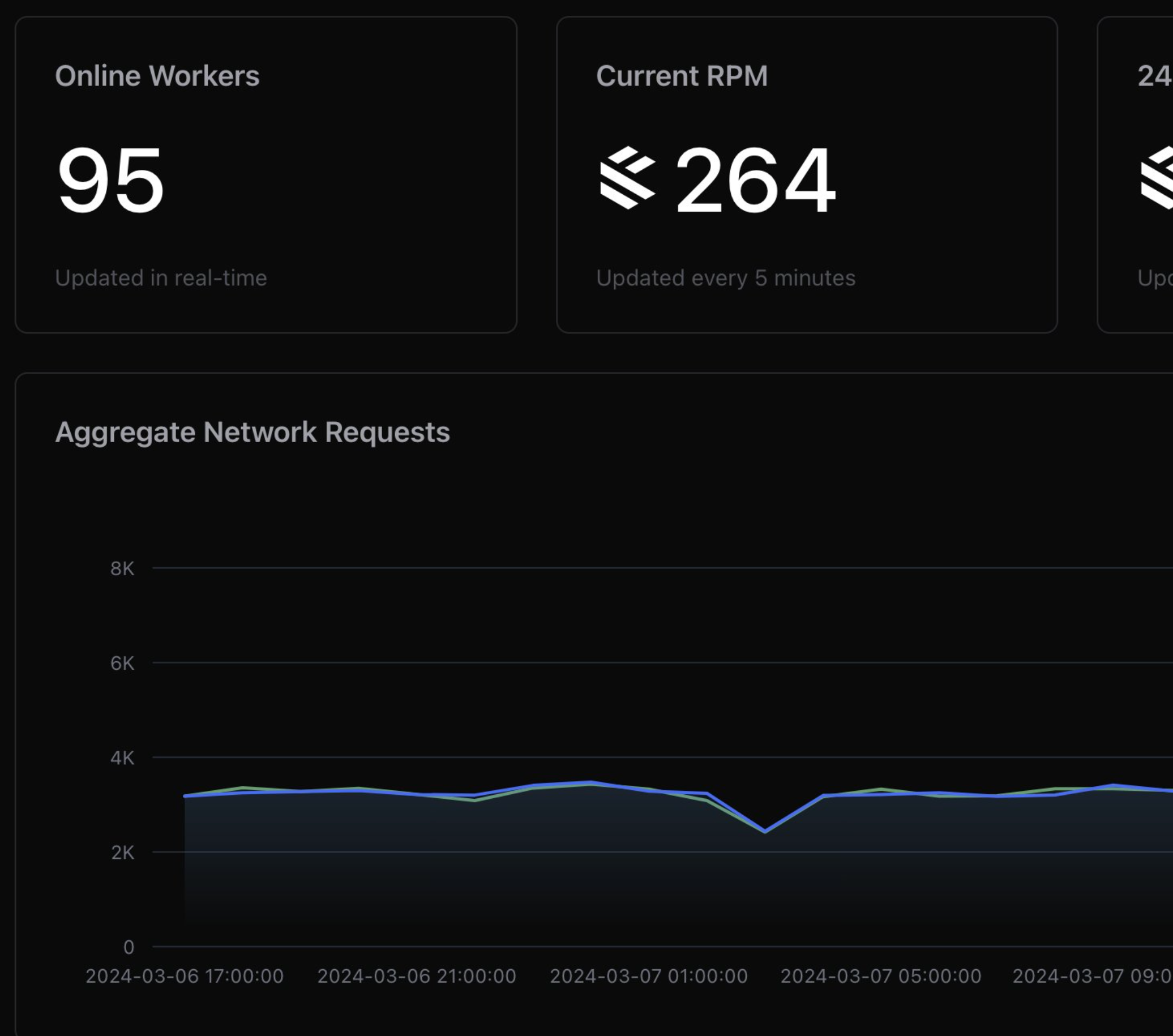

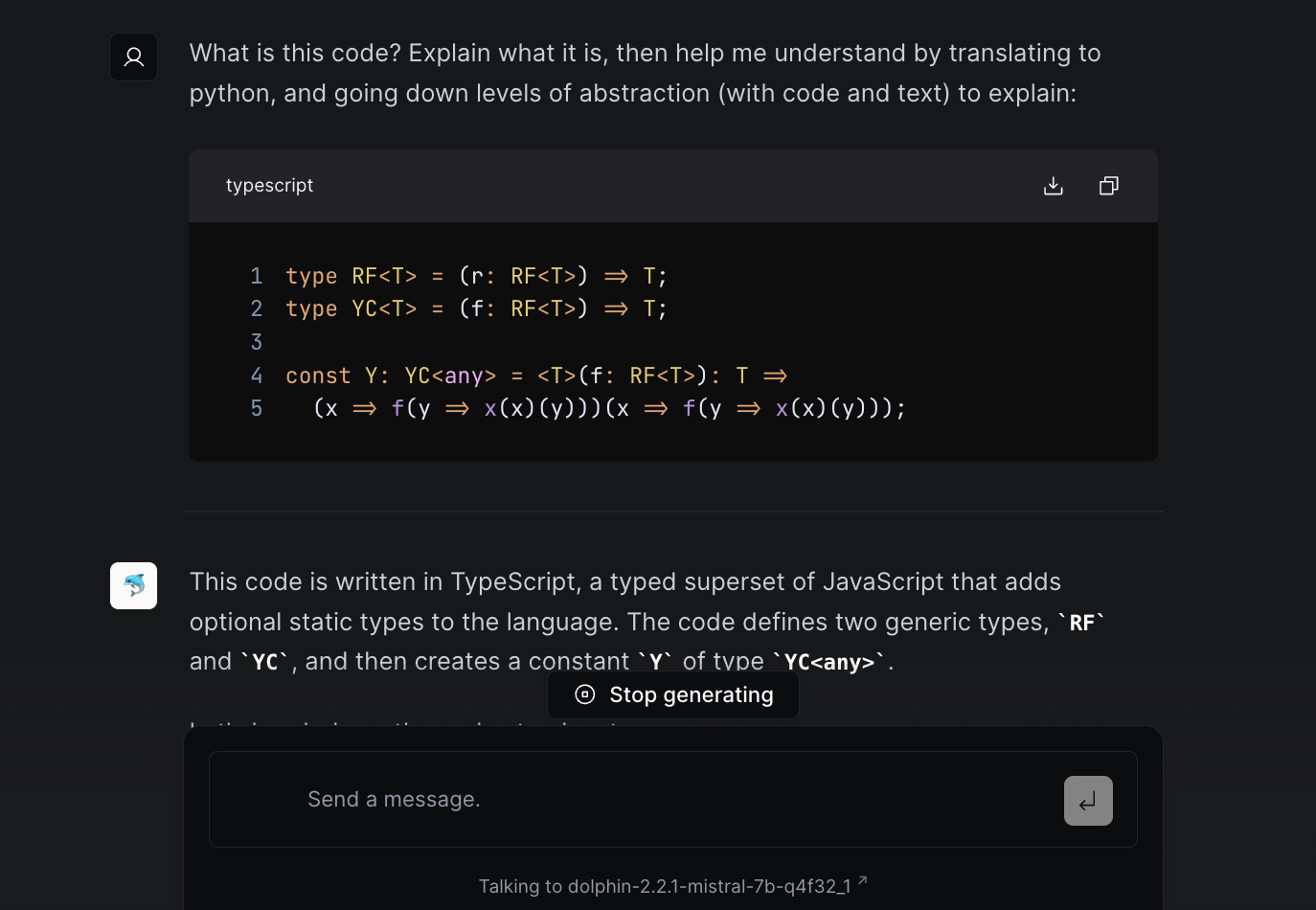

The people I know used to trace their lineage back five generations, but my circle now consists mostly of people like me who find themselves the emergent product of multiple cultures, raised by multiple people across the world, products of intersecting bubbles of media and narrative. The software I once used knew where it came from - I still remember Seetharaman Narayanan, Sid Meier and many others. Today, it's hard enough to keep track of the people behind my kernel past the namesake. I once knew exactly the person my milk came from - I knew which cow it came from, and I knew all the people involved in the process of getting it to my home every morning. Today, I'd be lucky to know the people involved in getting the software I design and write out to the hundreds of users on it.

The world at large - at least my corner of it - seems to be going through the same evolution. Somewheres and anywheres have become a strong distinction, and it seems to play no small part in the turmoil we find ourselves in as a species. I'm not making the argument here that this is bad - to the contrary, I think races and cultures producing something greater than themselves (and perhaps losing themselves a little in the process) is the right way to move forward. I've always held the belief that discourse is the best way forward in disagreement - especially when we disagree vehemently.

However, it bears examination - on a personal level - what this is doing to us. As the thread of history gets shorter and shorter, what does it mean for our psyches? What does it mean for the things we create and the relationships we build? Are we right in building smaller and smaller bubbles and tighter and tighter labels for ourselves, or is this an instinct to be fought? If it is, is it worth taking on the increased cognitive load in trying to maintain a social identity in relation to the world as a whole? If (as the aphorism goes) we are what we think others think we are, if we've always defined ourselves by each other, what is then an identity when these connections get wider and less simple?

I can't answer these questions in general, but I think they're worth asking. I can only try to explain the changes I've noticed in myself and my response to them. In my childhood and adolescence, my identity was defined by the community I grew up in, and the things that connected us. The connections were largely defined by craft (carpenters on my mother's side, farmers on my dad's) and location. We moved to border towns when I was 13, and looking back the identity further fractured when encountering a melting pot of different people and languages, coalescing around the places I could find enough people to call a community. I wasn't X's son or Y's grandson anymore, I was a Keralite, and a Malayalam-speaker. I moved to Singapore at 15, upon which I immediately became "Indian". I'm sure many expats will have had the same experience, but the interesting thing here is that the relative size of the community I connected my identity to stayed the same, at least in relation to the size of the populace I now inhabited.

I wonder if this is causal, if I kept finding the Goldilocks definition of identity that allowed me to connect to enough people but not too many. Moving forward, college further complicated this definition by giving me access to a new identity and community through shared education and values, one that I think has stayed somewhat post-graduation.

The one undercurrent that has stayed the same is the feeling of wanting to be from somewhere. This is a relatively new realization for me, as my feelings toward that somewhere have not always been positive. However, without that identification - I'm from a country, a college, a people - it becomes hard for me to place myself somewhere on the cultural map from which I can feel this way or that towards it. Of course, this is a definition that has gained fluidity as I've gotten older, but it makes me wonder if I can define myself without it.

What does this mean for our creations?

From this viewpoint, the idioms we've evolved in our communication make more sense - especially in the successful ones that we now try to emulate. It's hard for me to explain who makes my dinnerware, but it's an easier answer for my mind as to who makes the Falcon 9. We tend to trust products and companies (hello, Ivan from Notion!) that have provenance, grasping at even the illusion of one. We replicate it in our messaging - both personal and professional - as if to say, "trust me. I'm from somewhere." There's nothing inherently wrong with this, unless it's done without an understanding of why it's important to the person on the other end. Some of the best of us can endow a mail merge with the ring of provenance, but most of us simply lack the skill.

I believe the biggest problem comes when we try to establish a history without tying ourselves to it. If I present Greywing to you as a company that makes maritime software, I'm defining it by its present - what it does, instead of where it came from. If I introduce it to you as a maritime startup from Singapore, I have already attached communities that have established identities you may or may not agree with. You may not - as a consumer, reviewer, investor or casual observer - like what startup implies. You may not agree with Singapore. Or you might vehemently support both, and decide one way or the other, based on this declaration of history.

Neither is an issue in itself - but it becomes one when companies and people try to inject provenance without offending anyone. This leads to overlabeling - "non-white veganism" instead of "vegan" (this is actually a thing), where you try to identify with a community and add an increasing number of asterisks to carve out the segments you may not want to be seen associating with. We need to pick one or the other, trying to do both hurts more.

For this reason, I believe the best way forward - not the ideal, but I fail to see another option - is to contextualize provenance in much the same way we do in real life. Most of us don't have a single point of origin anymore, the same way we don't have a singular identity as defined from the external. It feels disingenuous to pretend otherwise. To a person from my hometown, I'm an NRI, an outsider. To a foreigner visiting my hometown with me, I'm a native. To my close friends, I'm simply me - they've known me from "that coffeehouse in Nepal" or "that common room in RC4" - with the complexity we must now find ways to contextualize and compress so we can keep functioning.

We are in the process of understanding what we are becoming. Perhaps this is a problem unique to a transitional generation like mine, or perhaps there are only transitional generations ahead as change accelerates itself. Either way, it is one I think is worth the discussion.

Not a newsletter