Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

cries the ancient mariner. Gone are days when the members of a ship made their own fates - today, the larger the vessel, the more complicated the fate of its crew.

Covid-19 has hit the world hard, but one of its least talked about and worst impacts is on the shipping industry. The global maritime network - a strong stand-in for globalization itself - relies on free movement of goods, supplies, people and transportation to maintain its fluidity. Similar to an assembly line, the slowest component holds up the entire process. Lose one, and everything grinds to a halt.

When most people think about it, the first thing on their minds is often the cargo - where will my packages go? What will happen to supplies? Are toilet paper cargo vessels (not a thing) exempt?

Yet the most important parts of this system are the men and women on board the vessels, living and working to move global trade. Crew on board a vessel follow a faimilar rotation of some weeks on, some off. Offshore rigs follow the same procedure except with fewer crew and longer hours due to space and resource constraints. Once you've finished your rotation, you're disembarked at the next port and flown home to your home airport. An onsigner is flown in to replace you, and the vessel moves on.

Simplifying massively, vessels exchange about 20% of their crew at each port call. If this doesn't happen, they overstay their contracts, get fatigued and make mistakes. This is what is happening around the world on a massive scale as I write this. Countries have locked their borders, sea and air. Airlines have stopped ferrying passengers and are cutting back on supply. The shipping industry is headed towards a humanitarian crisis that will ripple out into our lives on land.

As of our last estimate, over a million seafarers are trapped on vessels that are turning into offshore prisons of iron and steel, floating right next to dry land and fighting decreasing quality of life.

This is the problem we set out to solve two months ago at Greywing: giving crewmembers a way home. This was outside of what we did as a company, but every client we had could talk about nothing else. It made sense for us to do something.

We started Greywing with the intent of safeguarding the interests of the men and women that protected vessels. Now them and the people they protected were in trouble and so was the shipping industry. Contracts were extended on force majeure, but that couldn't last forever.

There was the collective hope that it would blow over, but it did not look that easy. We knew that even if the virus hit self-destruct tomorrow, we would still have a long road to a complex solution. Borders once closed take a long time to reopen fully. The shipping industry was headed straight for a wall, and we resolved to do what we could.

§CRY4

The first problem was information. A vessel goes to port to exchange goods and people, but its dictated by the nature and interest of the cargo more than its people. Not a problem when you could berth anyone practically anywhere, but now what we had was a quagmire of changing regulations. Clients recounted stories of flights being booked only to discover that port state control did not allow the crew change, and immigration and disembarkation procedures being complied with only to discover that transport (last mile and otherwise) was virtually impossible.

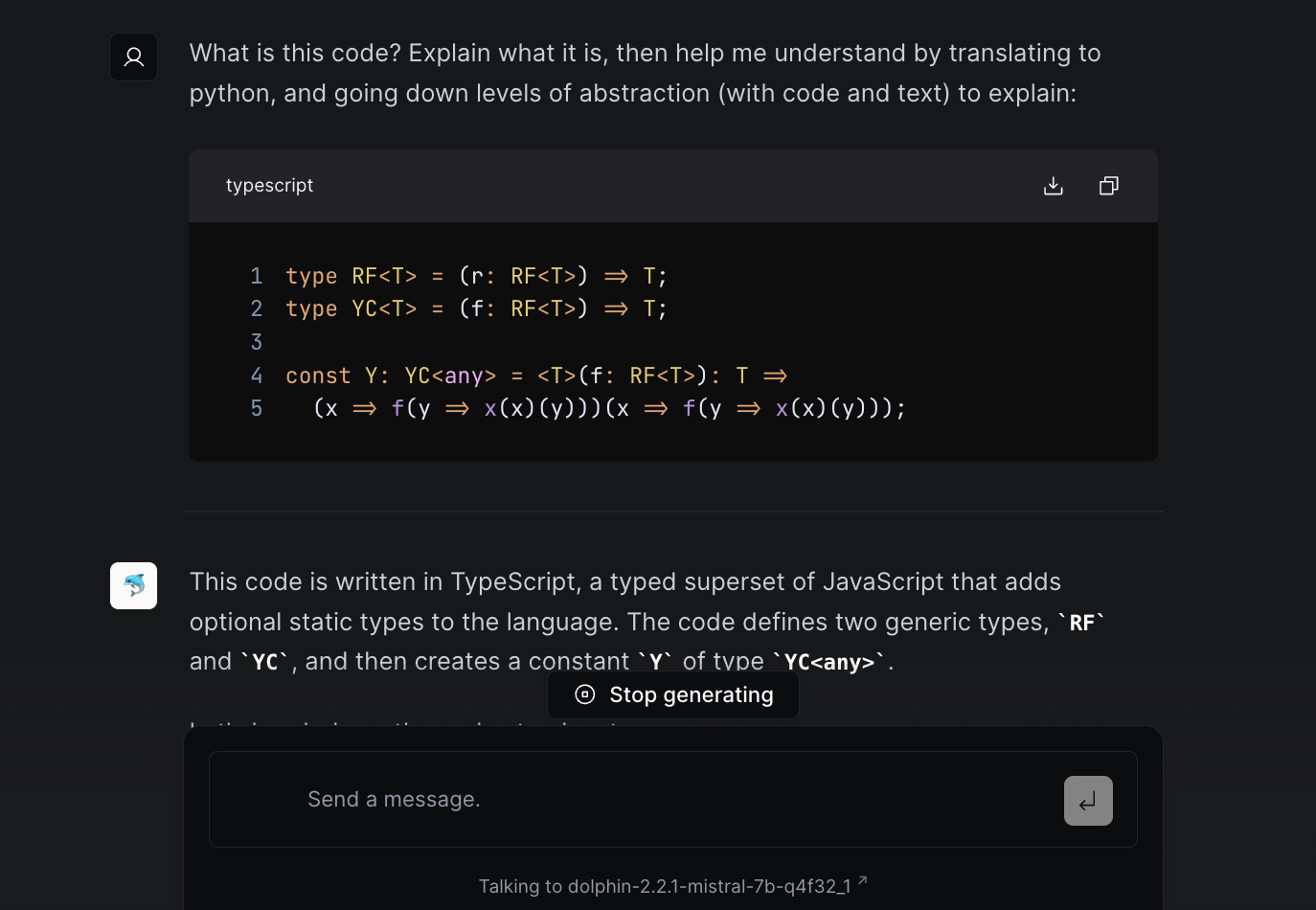

To us, this became an n-dimensional optimization problem. If we had structured data on port control, flight control, immigration restrictions, flight availability, crew member nationality and vessel voyage plan, we could chart a path for the vessel that would get its crew replaced.

Unforunately for us, none of those things, save for flight availability, existed in any form usable to a machine. The information was there, but buried in mountains of scanned pdfs and webpages with typos. Turning gigabytes of this information into actionable intelligence was hard, but we believed it was worth doing, and that we could do it. So we did.

CRY4 was a small intelligence tool we had built to provide piracy data to our clients quickly. Under the crisis' direction, it became a nexus of data sources, NLP and geospatial routing. We built comprehensive databases of ports, airports, flights and restrictions. After two long weeks and many sleepless nights, it was released in late March. The industry supported us and helped us launch, and we've done thousands of reports since then for vessels as they've worked the problem.

§Landfall

The second part of this problem was the information exchange between state authorities and a vessel, which have disaligned incentives in a crisis. Ordinarily they want the same thing - more port calls is more business. Now, countries were protecting their people and vessels became floating communities with no state taking responsibility for them.

Landfall was designed to use satellite and crew information about a vessel to estimate the risk of Covid-19 on board. It's meant to be the drawbridge between the two sides, so one side can manage the mountain of data and requests coming their way and the other can get through. Thanks to support from state authorities we've launched Landfall and risk assessed thousands of vessels. In the process we've found many surprising things about the maritime trade, but I'll save those for another post.

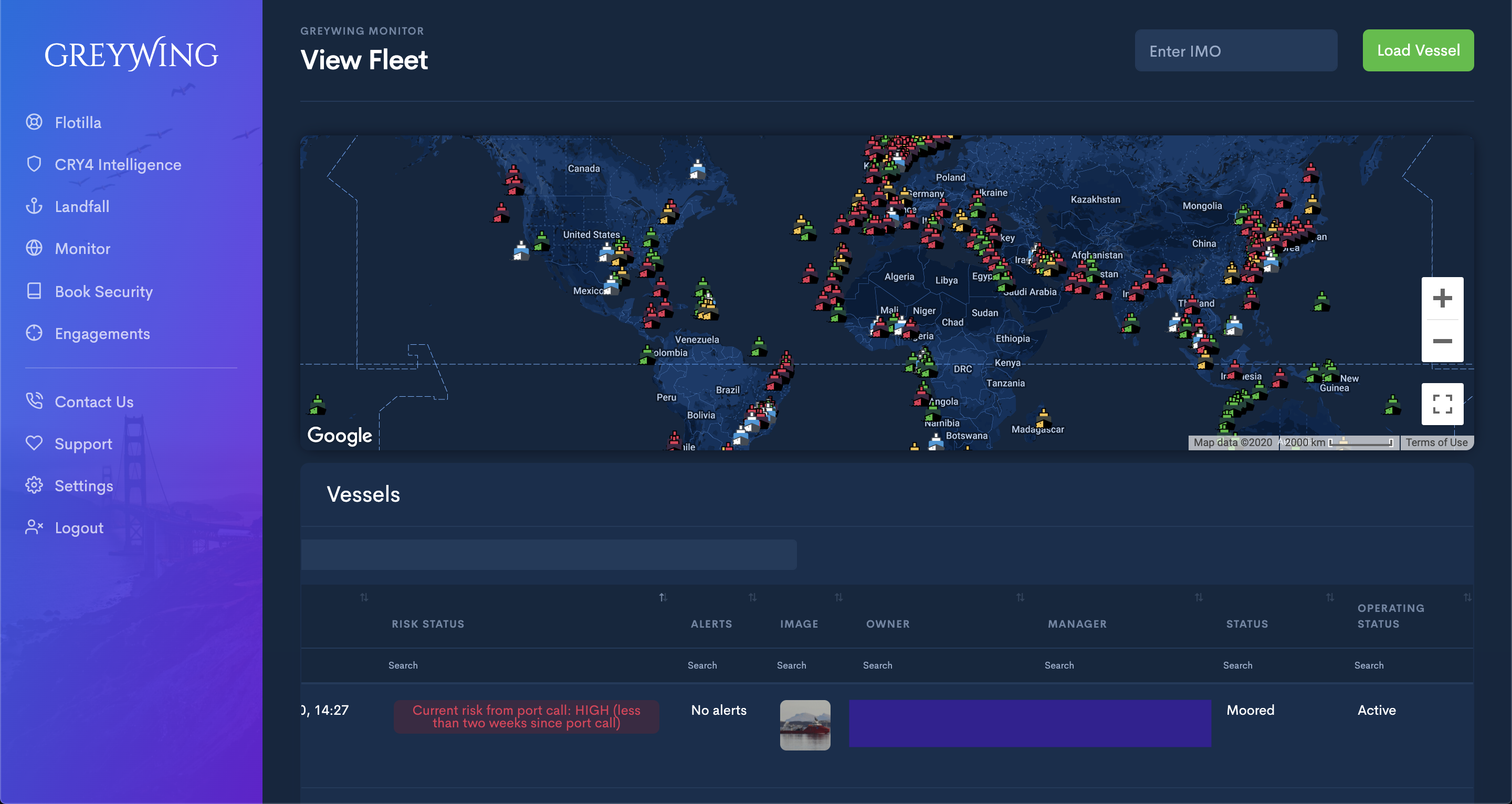

§Flotilla and Action

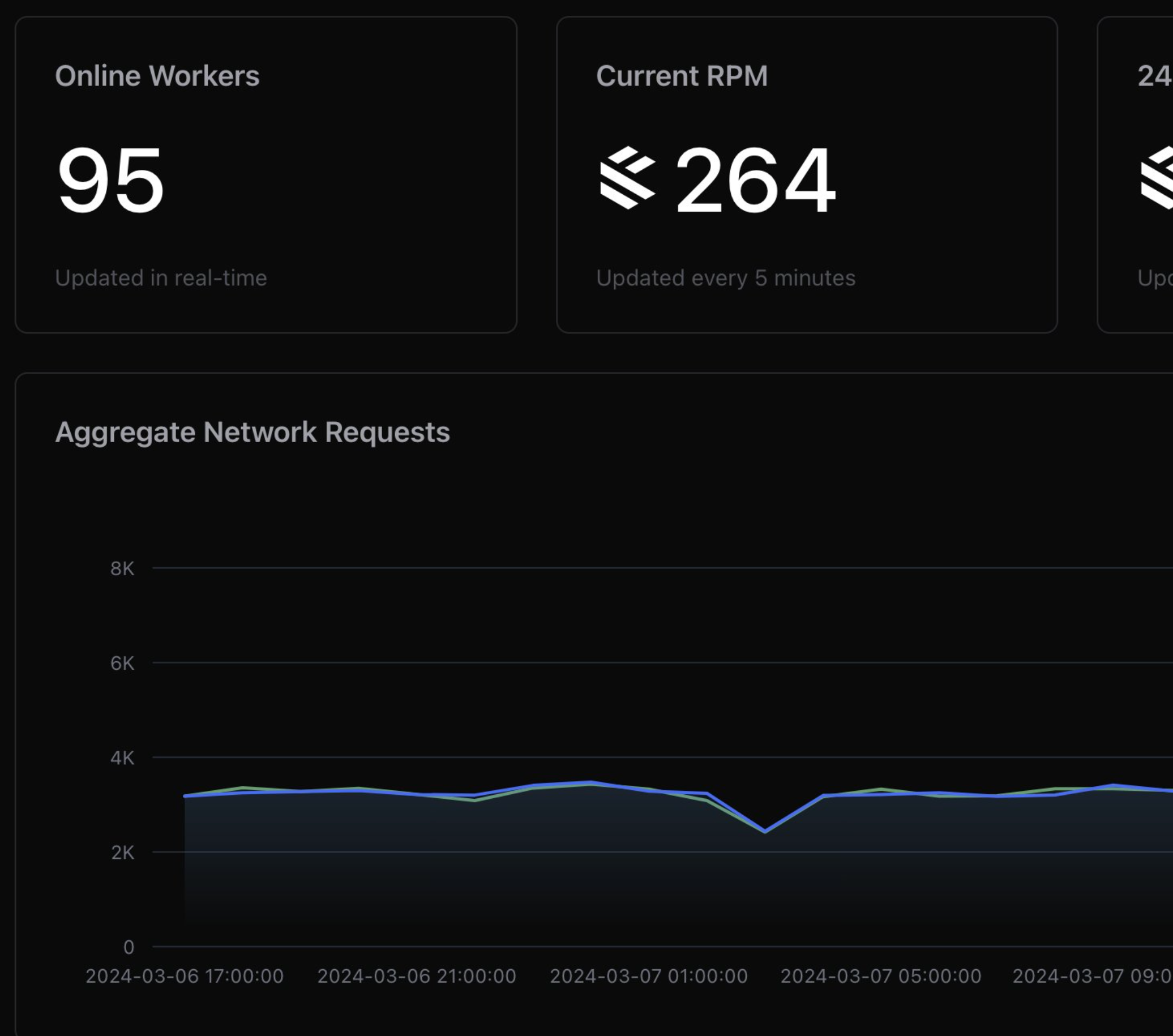

What we're now building and deploying completes this process - from information to action. Flotilla (which is nearing completion), allows vessel owners and state authorities to have a live overview of the hundreds of vessels in their charge, to highlight vessels that need attention and manage the sheer volume of data. Combined with charter flights booked automatically, we hope that in a week or two we can get to the point where a vessel master need only click a button before flights are booked for its crewmembers to their respective home airports. We're hoping the platform can enable strength in numbers and provide collective bargaining powers - and most importantly, a voice - to the crewmembers that ensure our countries and our worlds keep running.

I hope to write again with good news. This has been one of the most hectic periods of my life and our time as a company, but we've found unlimited motivation and energy in the impact of what we are a part of.

Not a newsletter