Working with geospatial data can be pretty complicated, with no easy answers. Over the last year, we have had to try and solve problems both small and big from a data perspective. We've deployed solutions ranging from completely handwritten code to large preexisting geospatial tools as a result. Hopefully this serves as a journal of the things we've run into, and as a reminder to always benchmark solutions - there rarely is a single size that fits all of them.

§Beginnings - doing it yourself

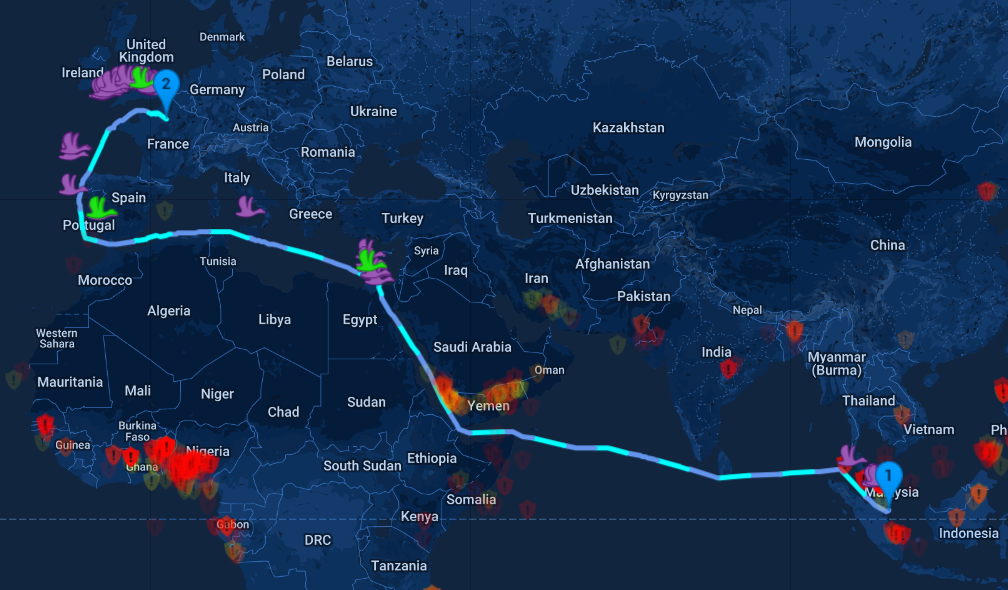

One of the first CPU-heavy things we built at Greywing was the maritime routing tool. Given two endpoints, we used a modified version of A* to route a vessel between points using a network of maritime routes and highways. This required that we build our own database of over 100,000 ports and map ocean routes at multiple levels of resolution, but having in-built routing came with a set of benefits: we could do it faster and better than most solutions, and the routing tool enabled us to build services on top of this predicted route. Over time, maritime routing has expanded to include custom legs and additional customization of the route, but the output is still the same: a list of GeoJSON paths that describe the route of a vessel for each day of its voyage. Here's an example route that takes a vessel from Singapore (SGSIN) to Paris (FRPAR):

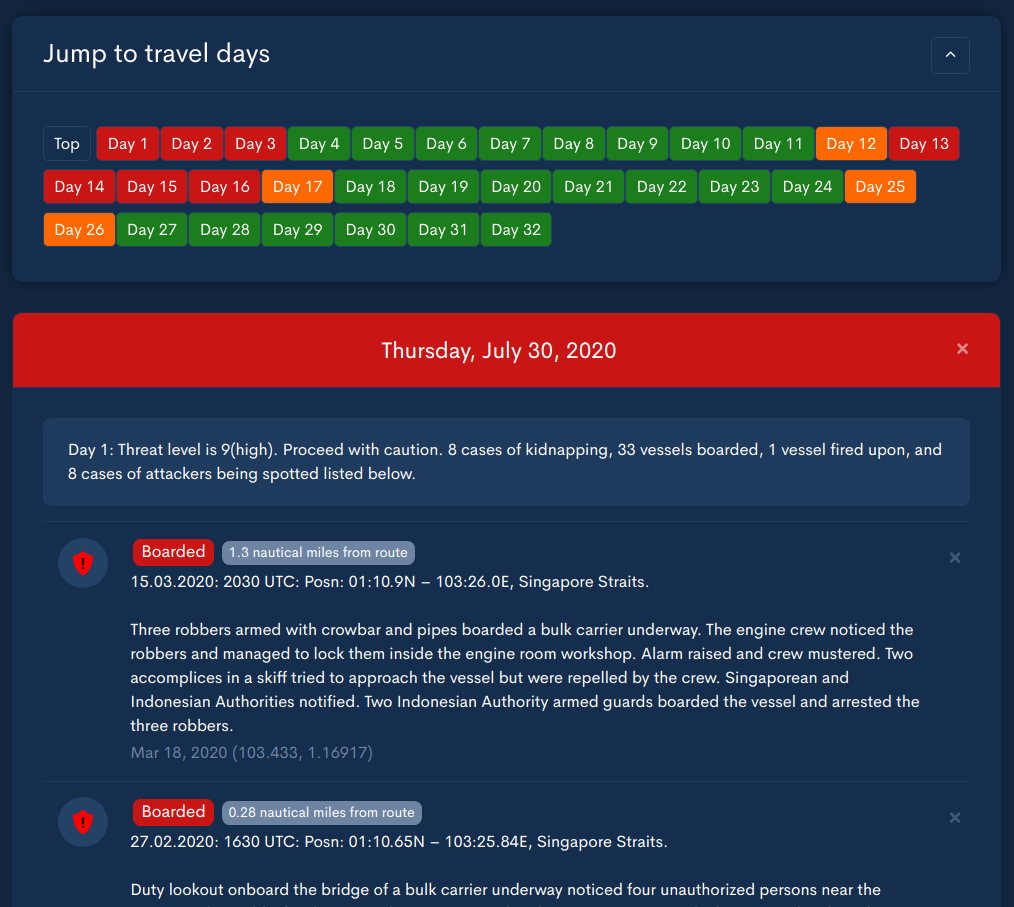

The first purpose of this route was in finding incidents of piracy and hijacking along the vessel route. Vessel managers used the events and the route plan to procure security where appropriate and put the vessel on high alert when transiting dangerous waters. Here's an example of an incident:

The searches started small and easy but as the database of incidents grew to over 5000 (or OVER 9000), we had to build a better solution. Dividing the map into b-tree like segments and fencing them in to find matches enabled us to quickly eliminate points that were far outside the route of interest in real-enough time bounds for our application (about 250ms).

Due to the complex nature of these routes, this was still a complex job - for us it involved taking each line segment and comparing it to points nearby to find the distance. This was something we knew to be low-performance, but it worked, and well enough for an exploratory solution. Further slowdowns came when we switched from simple great-circle distance (points on a sphere) to accurate Geographical Distance. There are again many ways of accomplishing this. Vincenty distance fails for antipodal points, but antipodal points would be too far from the route to matter. Karney's algorithm provides a better result, but was far too slow to perform large queries.

We found that using great-circle to eliminate points before labelling the points with accurate distance provided faster searches with accurate final results. A point or two might fall through the initial filter - we might miss a point that was outside the great-circle distance but inside a more accurate estimate - but the general patterns of maritime risk still held strong for route planning and risk estimation. As an example, here's what Day 1 looks like for the route above:

§Proximity Ports - standing on the shoulders of giants

I've covered the mounting humanitarian crisis that is crew change in a different post, which goes into detail about why this is currently a very pressing issue for the shipping industry. In trying to tackle crew changes - figuring out where in a sea of changing restrictions to take crew out and put more on - we realised that we had the data needed to provide actionable insights to route vessels, in a way that only we could.

We had already aggregated and cleaned data about past crew changes, port restrictions, visa restrictions and flight restrictions. Most of this information was public, but only a digital platform could query thousands of these points in multiple dimensions of fit to find the right places. The next target became to build a system that would analyze the vessel route and return the most valid ports for a crew change, factoring in all known data about the vessel, ports and countries. Called proximity port alerts, rolling this out would reduce the man-hours needed to find a valid route by orders of magnitude.

The first thing we did was to use the existing algorithm for piracy on analyzing ports. It would be an understatement to say it did poorly.

Route Length: 500 nm

Buffer Size: 10 nm

Port Query runtime: 20.5s

Ports Queried: 120000

Ports Selected: 250

Did I mention this is using great-circle distance? The next step was to stop just short of using full GIS tools,

and make use of the native earthdistance and cube extensions for Postgres. I'm still inexperienced with GIS, and

the breadth of standards and additional code complexity posed a problem. We did not want to integrate something into the stack when we didn't understand it.

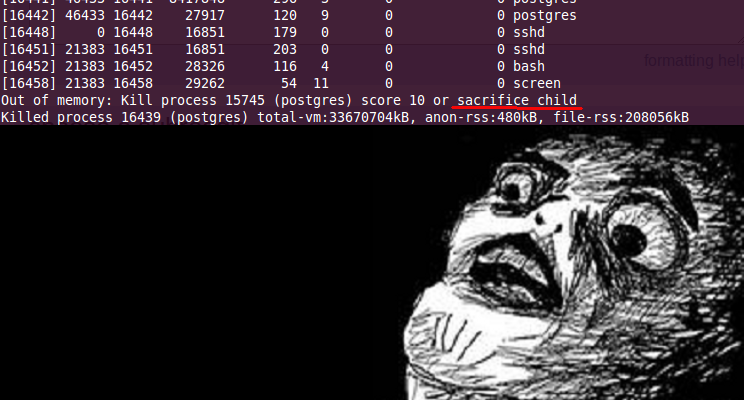

I will never stop championing Postgres as the ideal database, especially if you don't know what you're doing - even more so if you do not know what you will be doing. It's light and fast for most use cases, and it's a database you can fully grow into. Sure, it occasionally demands child sacrifices, but that's the price to pay for a good relational data store.

Earthdistance is a native extension for Postgres that performs simple point to point distance queries and filters. This made distance comparison easier and more optimized, even without specific indices for the queries being made. Things looked a little better, and with a reduction in complexity.

Route Length: 500 nm

Buffer Size: 10 nm

Port Query runtime: 5s

Ports Queried: 120000

Ports Selected: 248

Earthdistance uses great-circle distance, and it seems our custom algorithm disagrees slightly. We ran multiple batches of queries to ensure that this difference was minimal, but it was still too slow for our use case.

Querying for nearest ports is only the first part of the equation, and the second - evaluating each port for crew change suitability - was just as heavy on load. We couldn't afford to spend this much time just on the filter.

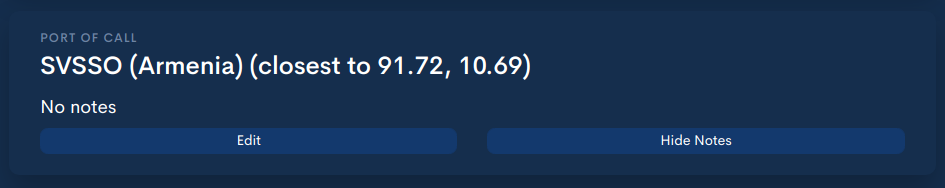

However, on a different part of the platform, using earthdistance made a big difference. We implemented waypoint matching some time ago (using straightforward search) to match unlabelled lat/long coordinates to ports. This allowed us to provide port-related information to routes with lat/longs and no ports.

Using waypoint matching, routes that go through unrecognized or unspecified locations can still be labelled with useful data, and using earthdistance reduced the runtime of this query by an order of magnitude (10ms to under 1ms).

However, these were simpler queries based on the distance between two points while proximity port alerts required us to query distances from complex paths to thousands of ports. In the end, we bit the bullet and took the time to understand PostGIS. Before I go into detail, I can tell you that PostGIS is a beast. Perhaps it's not complete by QGIS and ArcGIS standards, but it contained more than enough tools for our use-cases.

PostGIS is essentially earthdistance on steroids, with a lot more geospatial functions and operations, supporting more formats and with a higher degree of optimizations to be used on larger datasets. Getting started proved relatively easy: with support for GeoJSON and easy path queries, we first converted our paths to PostGIS' internal representation using ST_GeomFromGeoJSON, then ran it against the database of ports for matches within a certain range. The results exceeded expectations:

Route Length: 500 nm

Buffer Size: 10 nm

Port Query runtime: 0.01s

Ports Queried: 120000

Ports Selected: 240

Not to mention that the results were computed using accurate geographical distance and thus needed no further correction. It seemed that the select queries were also heavily optimized - labelling the distances first and filtering on them took over 2 seconds, while filtering first and labelling took less than a millisecond.

There is a write-up on how this was done, but it's now lost to code-rot and the general insistence of the web on changing links. I was able to find it on The Internet Archive, and it's well worth the read.

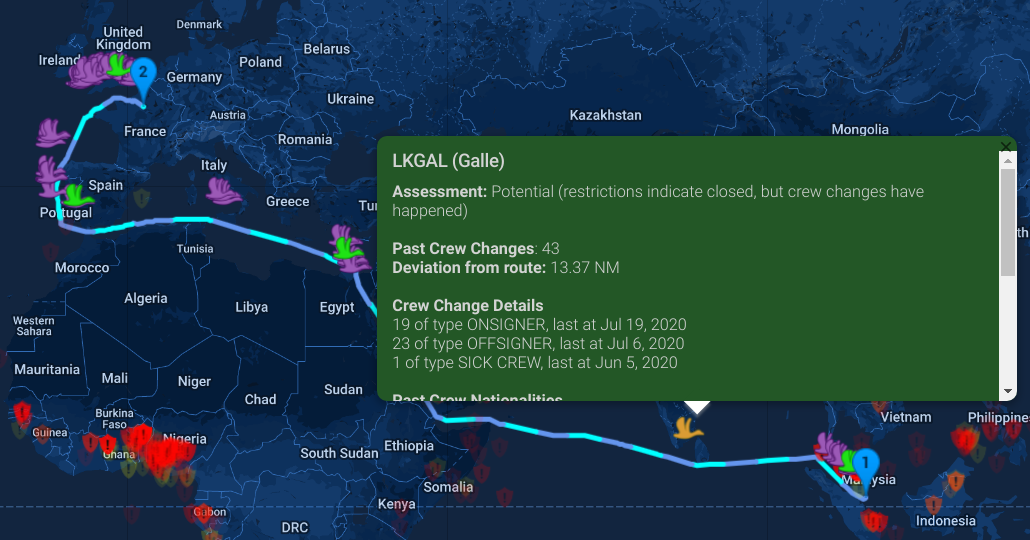

Needless to say, we integrated PostGIS into our stack and proximity ports were released a few weeks ago. You can now route a vessel and immediately see which ports have had past crew changes, which ones are open, and which ones are closed but, surprisingly, still conducting crewing operations. Visa information is laid in from the crew composition of each vessel, and the nationalities of past crew changes are retrieved. Each port can be evaluated at a single glance for suitability:

Green wings indicate open ports conducting crew changes, purple wings indicate open ports that have not conducted a crew change, and orange wings (when they appear) show closed ports that seem to be conducting crew changes.

Since it worked well for proximity port alerts, and since it was already in our stack, we set about benchmarking it against all the other places the previous geo-search heuristic had been in operation. However, we found that it was slower for both the waypoint matching as well as the piracy indicator.

As an example, this is one of the results of our benchmark of waypoint matching:

Waypoint Matching with custom module: 9.1 ms

Waypoint Matching with earthdistance: 2 ms

Waypoint Matching with PostGIS : 8.5 ms

The results varied with PostGIS sometimes outperforming our internal algorithm, but they were always beaten by earthdistance.

These are the results for piracy searches:

Incident search with custom module: 500 ms

Incident search with earthdistance: 5084 ms

Incident search with PostGIS : 3000 ms

For some context, waypoint matching usually compares a handful of waypoints at the most against the port database, piracy searches compare an entire route against 2000 piracy incidents, and proximity ports compares a more complex route against >100,000 ports and airports before labelling the results for suitability. We were surprised to find that our custom solution, earthdistance, and PostGIS all had sweet spots that served specific problems.

This makes some sense as our custom search module was initially written for piracy, but it could well be that we haven't optimized PostGIS to the fullest extent, and it's something we're working on. But it makes sense to us that the three problems are different in complexity and requirements, and as we get to larger and larger datasets we may find that one size fits all - just not for now.

(Something I will say about PostGIS, is that setting it up on our UNIX machines in the cloud was a breeze. No problems whatsoever. In stark contrast, it took me a week to get it barely functional on my Mac. Brew refused to link my PostGIS installation with Postgres, insisting on installing the same version to a different folder but refusing to link that to system path (going so far as to keep removing it). Compiling PostGIS from source worked, but brew continued to remove PostGIS' feeble attempts to link itself to brew's Postgres, until I gave up and recompiled both outside of brew. There were enough problems along the way that were entirely El Capitan's fault to hasten my exit from the crumbling Macbook developer ecosystem. More on that later.)

Not a newsletter