Once again, AI had no real hand in writing this guide (except the Glossary). This has been a work in progress for weeks as we've built bigger and bigger datasets and benchmarks at Southbridge. This guide is informed by everything I've learned, covering the most important and the most practical, while keeping things simple and understandable.

We'll work through examples, and I'm hoping to put down everything important I know for my own reference. I find that the simpler you can make something, the less it rots as models, concepts and technologies change.

Turns out evals today are in the same place that prompting was in 2022 (when I wrote Everything I'll forget about prompting) for the same reason.

No one questions the importance of evals. There are innumerable posts and guides (a lot of them really good, and linked at the end). You can find guides going over why evals are important, why you need them to close the feedback loop on your products, why you shouldn't be doing anything in AI land without them. Everyone has a FOAF that's built an LLM product with seven nines using evals.

Yet there aren't any that tell you how to do them. The best ones I could find have a few prompts as an example, some theory, but the rest is left as an exercise to the reader.

If you look wide and deep, you'll find prompts (some of which are wrong), but nothing that covers the end-to-end process of taking a task, breaking it down, designing evals, picking models, and closing the iterative loop.

We know we need to do this eventually (credit to Eugene Yan).

But how do you write the evals?

§Why is this so difficult?

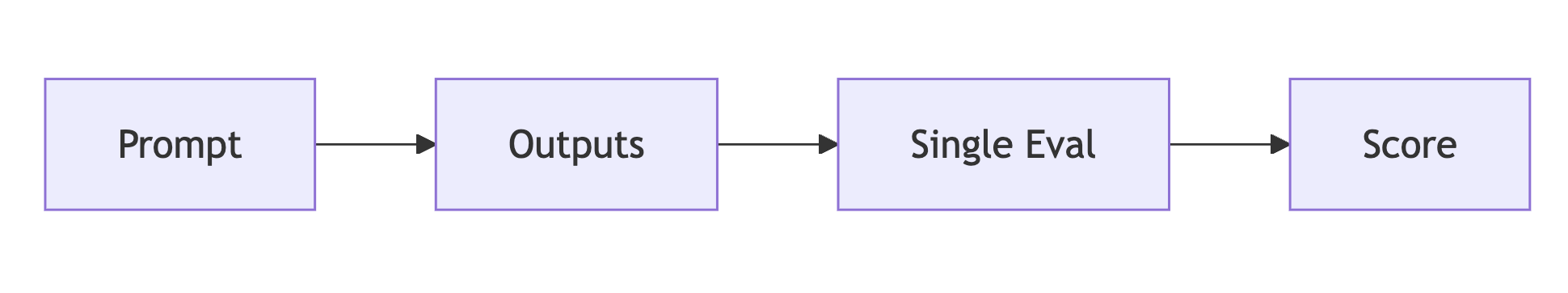

Prima facie, this doesn't seem to be a big problem. Take your prompt, generate outputs, save them somewhere, write some eval prompts, run them and rinse until you're passing some threshold. Right? Not so much.

Evaluating AI systems will remain increasingly difficult due to this simple causal chain:

- AI is probabilistic in nature: Models are non-deterministic, often chaotic systems. A single word modified in a prompt or input can have unpredictable results in the output.

- Measurements need to be deterministic: Chaotic measurements are as good as no measurement at all. In the world of AI, this means either incredibly simple measurements (like counting the number of words in an output), or building systems that are statistically stable at scale. We usually only have the second option, because of the next reason.

- Models are getting smarter: As they get smarter, the tasks we need them to do get more complex. They go from “What are the company names in this document” to “evaluate the performance of company A considering their earnings reports and tweets”. We move further and further into NP-hard territory, where verification isn't easy.

- LLMs are the only real NP-hard judge: If you set aside human judgement (which is very hard and expensive to do at scale), LLMs and AI models are our only real avenue to measure their own success on human-level, NP-hard tasks.

- Judge models are usually dumber than task models: In (almost) every production system I've seen, task models are often the smartest you can afford, while judge models are likely the cheapest you can afford to run repeatedly. This significantly increases the difficulty of the problem.

We can distill the problem at the heart of evals into this simple formulation:

§How do you get a dumber intelligence to verify the output of a smarter intelligence, such that the results are a statistically stable proxy of success?

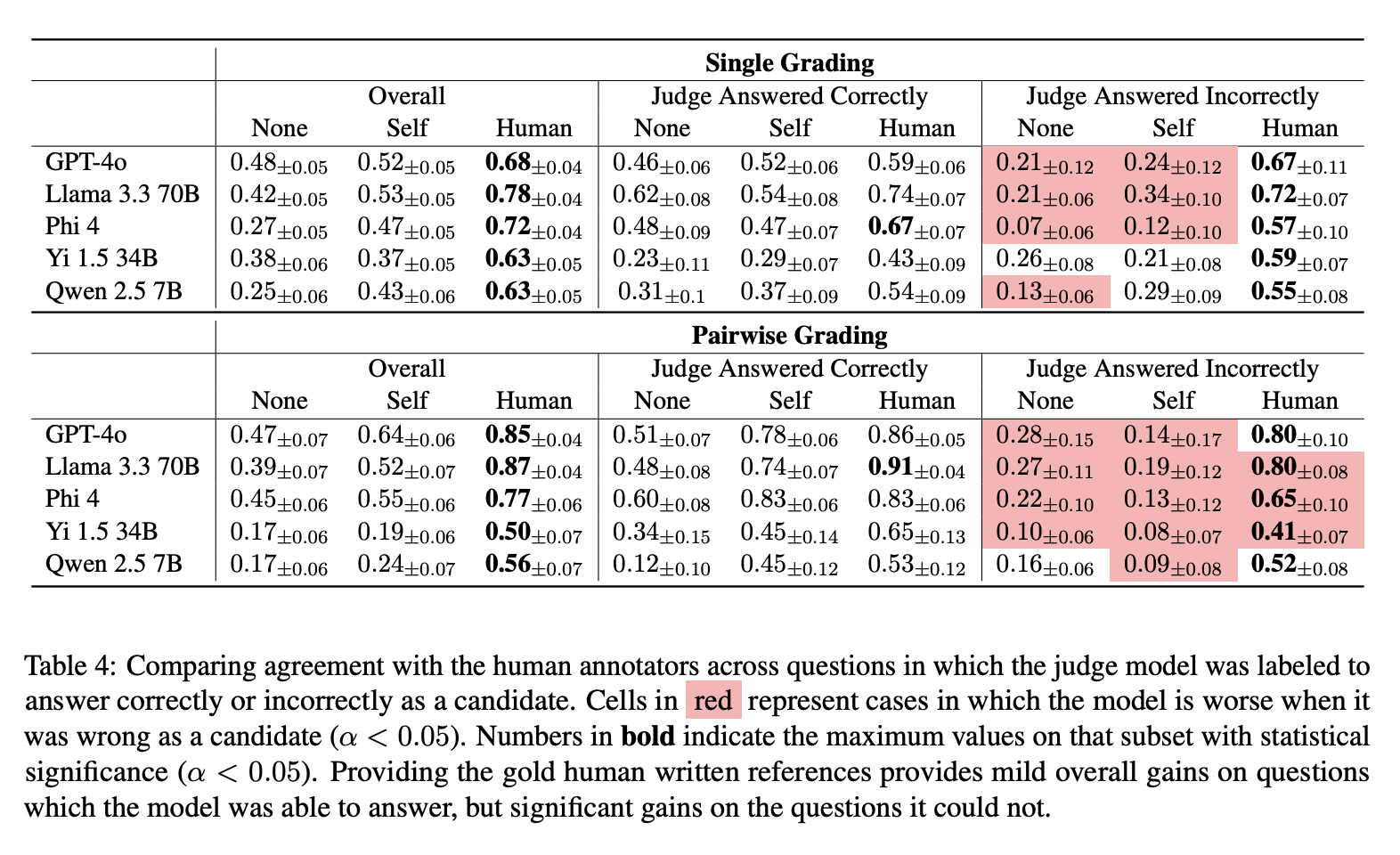

This is a pretty big problem. There is some research suggesting that an LLM's ability to answer a question itself is closely related to its own ability to judge an answer.

There are more problems:

§How do you introduce evaluation into an AI system without adding to its complexity?

When you measure a voltage with a multimeter, you're also measuring the multimeter. In the same way, the more complex your eval, the higher the chance that you're measuring variations and issues in your eval as much as the task itself.

We've never had these problems in software testing with such criticality. Unfortunately, we (software engineers) are often happy to think of evals as unit tests, and to tack on complexity trying to solve problems that really need better workflows and thought.

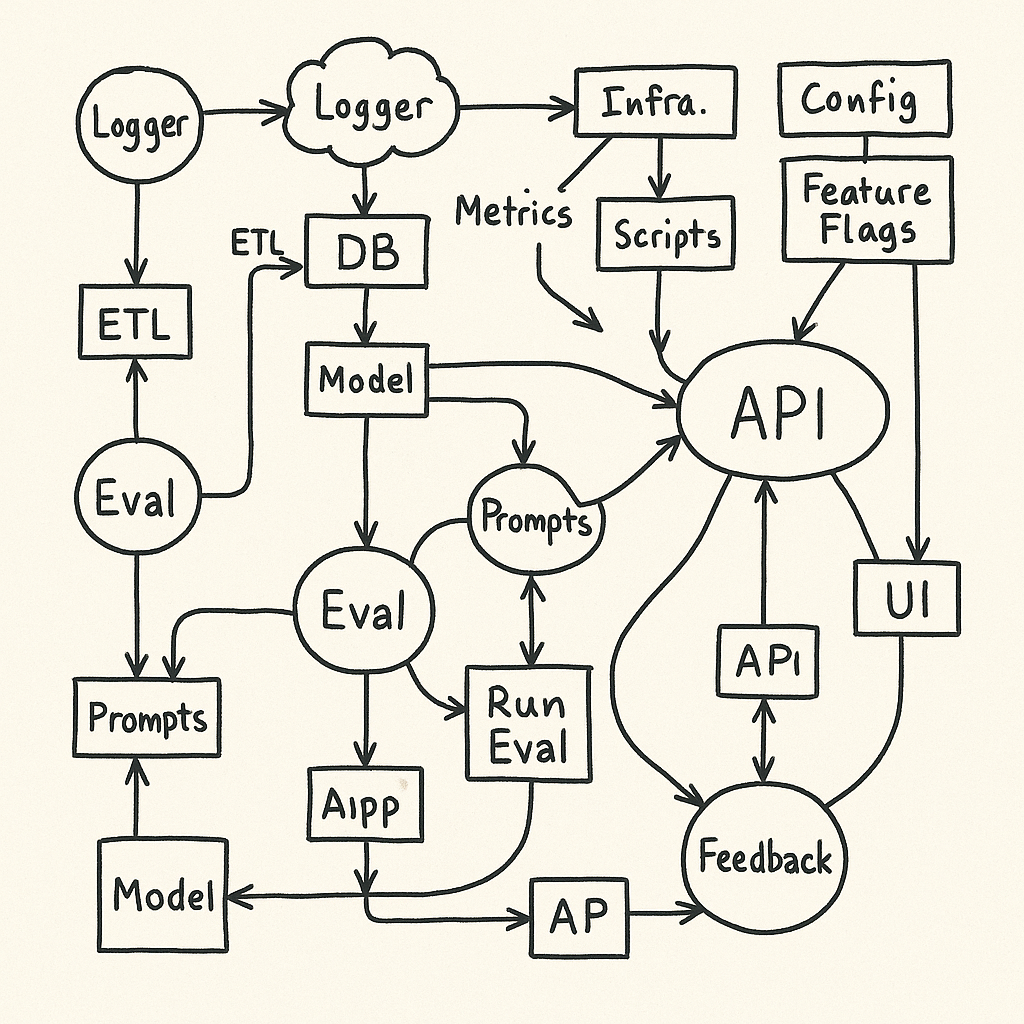

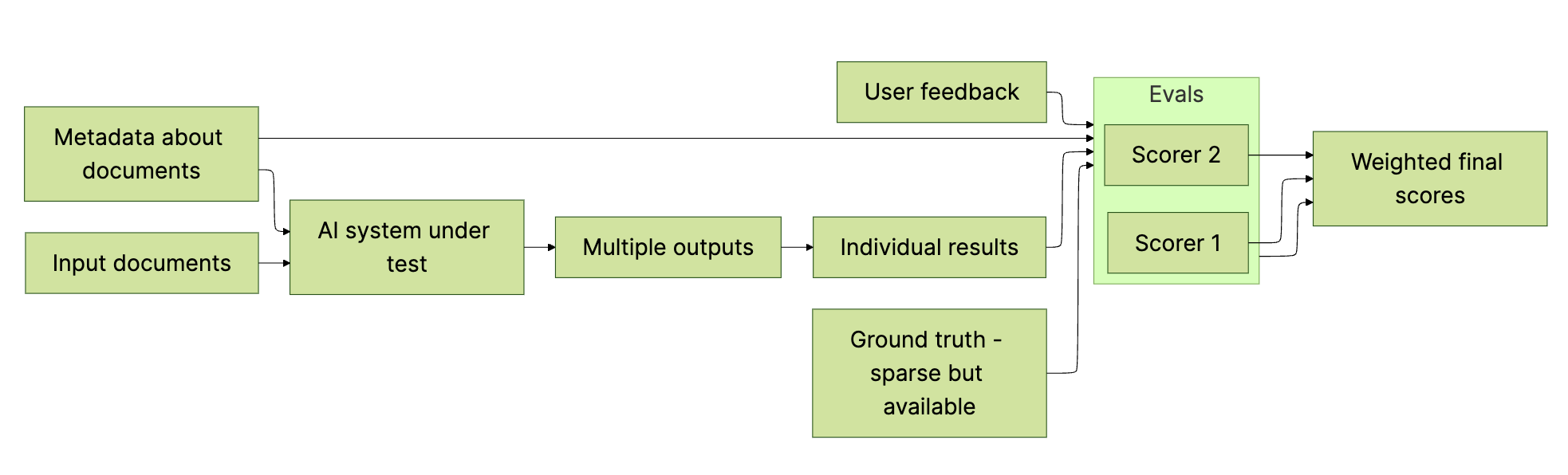

This is how we end up at complex block diagrams like this one (which I made up not to really point fingers). Starting here robs attention and focus from the core issue of figuring out what needs to be measured, how to measure it stably, and whether the measurement is a real proxy for actual success. We end up wanting evals without really wanting to make them or spend time, and it shows.

So there are a lot of problems to consider, leaving aside smaller ones like:

- What platform do I use?

- Which model do I use as a judge?

- Do I use scores?

- How many evals should I have?

We'll cover all of those from a practitioner's standpoint in this guide, starting with the question I hear the most.

Quick definitions before I start. A prompt here is usually text that instructs an AI model to do something, task is the main prompt plus outputs under test, scorer is a specific evaluation of a specific thing, and evals usually refers to multiple scorers or multiple runs of the same scorer.

§What platform should I use?

This is the wrong question to ask at the beginning. I'll set it aside for the end, and you should do the same. TAOCP is handy here:

If you're starting to write evals, the platform doesn't matter - Python (ideally Typescript) code in a loop will do you fine.

Most platforms can also be harmful at this stage, because they provide an opinionated methodology that may or may not fit your actual task. By the time you realise you were shoving a banana into a keyhole, vendor lock-in will have kicked in.

Moreover, most platforms also offer predefined eval prompts and scorers, and these are a really bad idea. These prompts have no context on your task, situation or outcomes, and its easy to be misled by helpful names like Factuality and Truthfulness.

Here's a better question to ask.

§What's the first thing I need?

The first step is to create a dataset. In very simple terms, a dataset is a set of input-output pairs organized into rows. Basically a spreadsheet - I wouldn't overcomplicate it at this point.

Each line should be one example of the thing you're testing. The sample under test. Not more, not less. Once you have that, make sure you have the right metadata attached. This will make your life way, way easier.

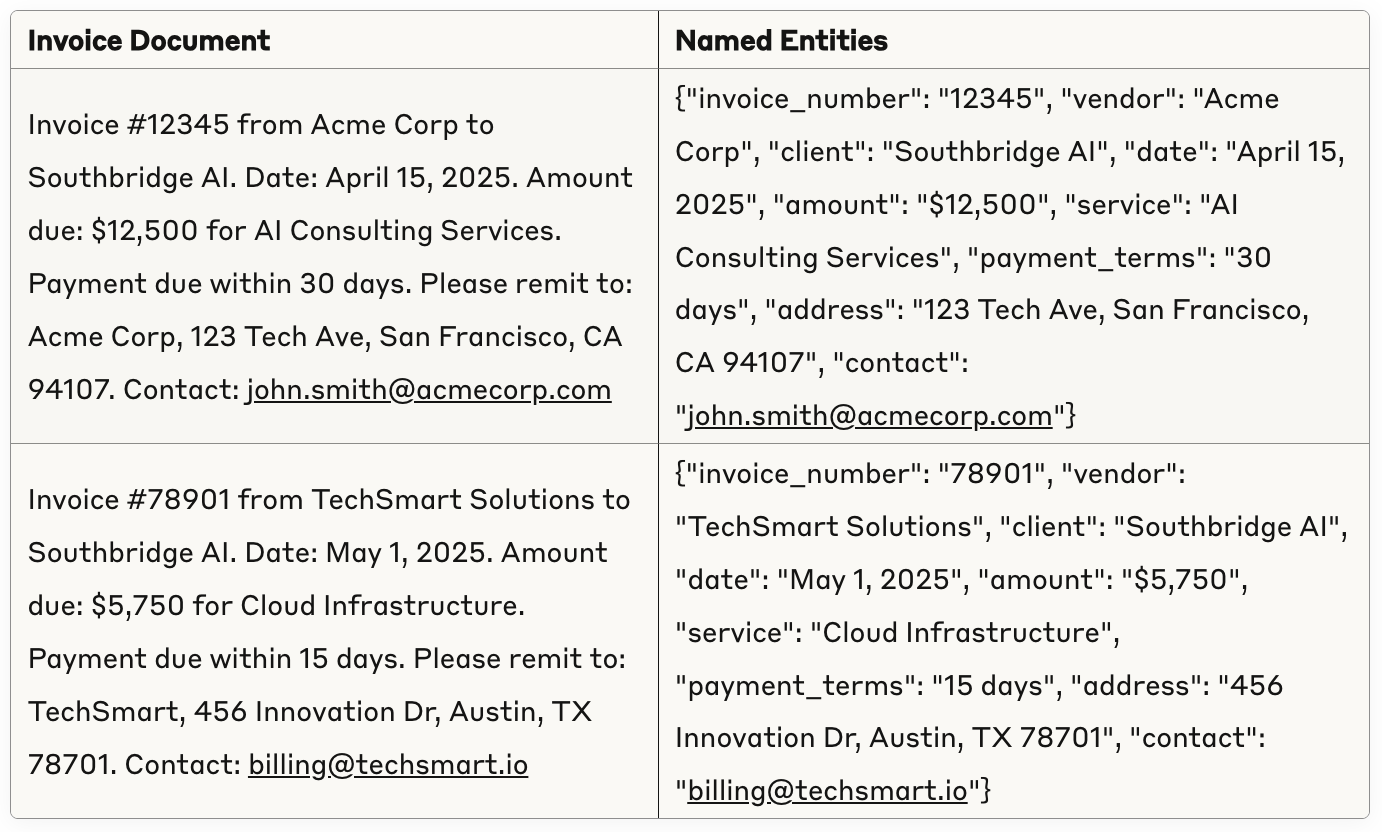

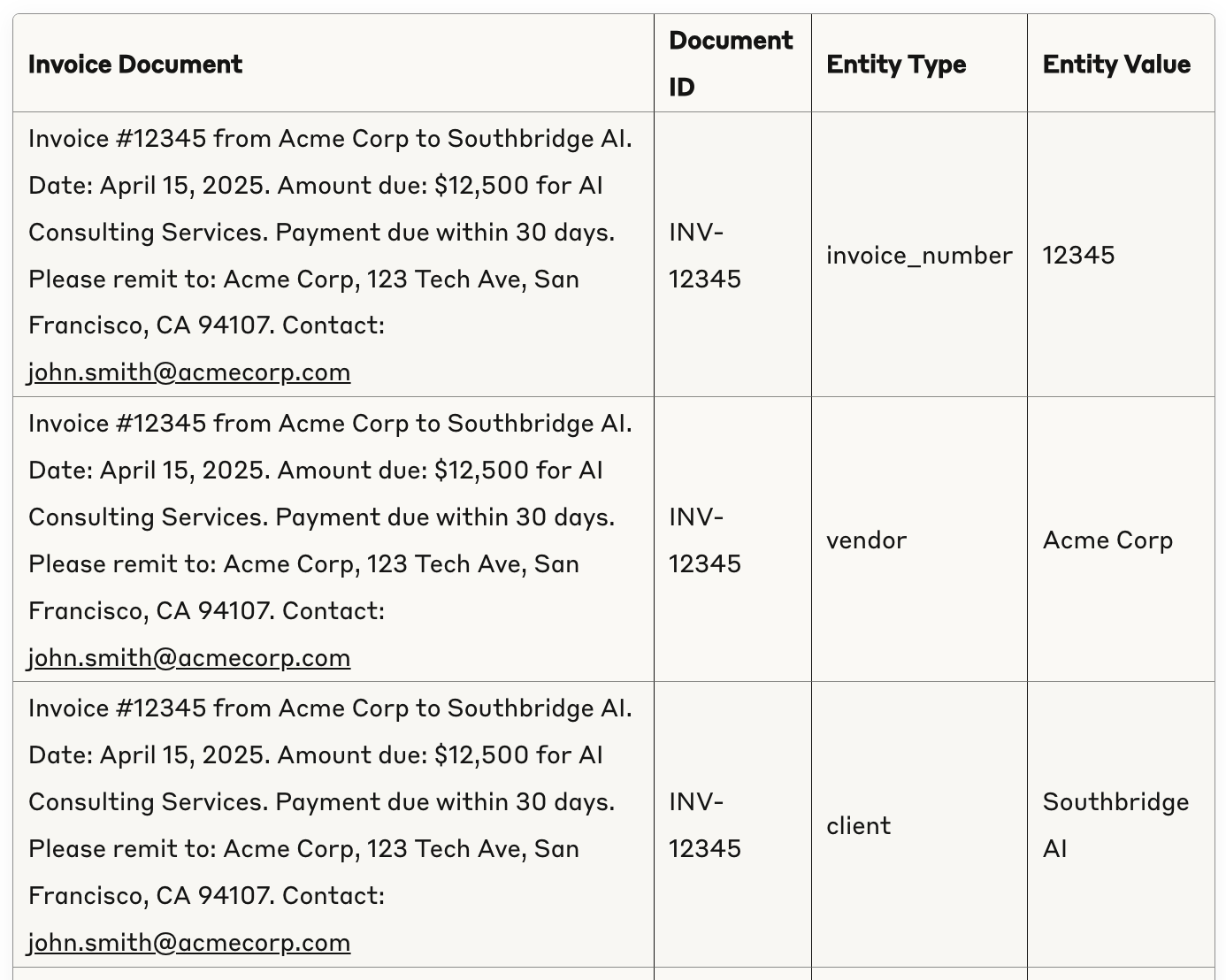

Here's an example. Let's say you're extracting named things (NER) from documents. It can be tempting to take an input/output pair and call that a line in your dataset - something like this:

However, you need more rows to isolate each entity (which already grows you out of the capabilities of most platforms). Batch-measuring results is not a good idea at the beginning - you want more control, better accuracy and less task complexity in the eval. There was a time when costs were so high you'd have to, but today it's far better to measure things individually. Here's a better version:

It's tempting to take all of the entities, and simply ask an LLM how well the process went - this is after all what you would be doing if you had a human evaluator. You'd give them some rubric, and ask them to grade based on how complete the extraction was.

You're evaluating entity extraction from invoices.

<document>

Invoice #12345 from Acme Corp to Southbridge AI. Date: April 15, 2025. Amount due: $12,500 for AI Consulting Services. Payment due within 30 days. Please remit to: Acme Corp, 123 Tech Ave, San Francisco, CA 94107. Contact: john.smith@acmecorp.com

</document>

<extracted_entities>

{

"invoice_number": "12345",

"vendor": "Acme Corp",

"client": "Southbridge AI",

"date": "April 15, 2025",

"amount": "$12,500",

"service": "AI Consulting Services",

"payment_terms": "30 days",

"address": "123 Tech Ave, San Francisco, CA 94107",

"contact": "john.smith@acmecorp.com"

}

</extracted_entities>

Grade the extraction on a scale from 1 to 10 and explain your reasoning.

This might work, but it's a better idea to eval each extracted entity. Use batch outputs only when the results relate to each other.

This is one of the cases where the AI-human analogies fail. Take this article for example. So many people helped proofread, edit, illustrate and eval this post. If I asked them to eval each individual paragraph in parallel, I'd likely have fewer friends than I do now. AIs on the other hand are happy - and cheap enough - to do it, which means I can have a large number of simpler eval runs I can aggregate, instead of one large, unstable prompt that adds complexity to the system.

§How complex does my system need to be?

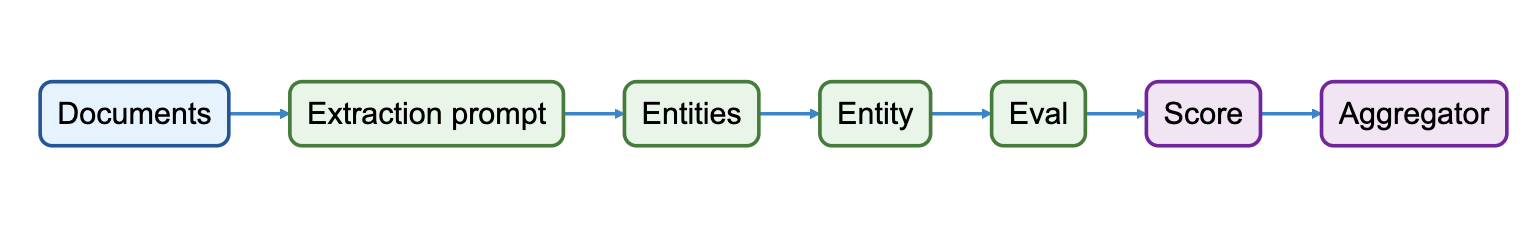

An eval system is a mix of probabilistic pieces under test, and deterministic components - all of which introduce different levels of steering and control issues. Think of an entity extraction prompt - let's break it down. Here's the simplest version (four lines of mermaid):

Unfortunately you trade control and predictability here for complexity. How do you accurately measure how many invoices you're extracting? Is the LLM failing at particular types of documents? Your eval is one giant prompt. How do you tune it when you find out it has problems?

Here's what something like this might look in production, about a year into an actual product:

Jumping straight to this (because you read about Harvey) is often a bad idea - it's a lot like buying a fully furnished living room from a store for your house. You don't need these things yet, and most of them will just eventually get in your way and stub your toes. Add things as you need them, but here's a better place to start:

This makes your evals simpler - they're just measuring a single entity against a document/corpus, significantly reducing task complexity. Join things together on the other side.

§Who can be my judge?

If you have any LLMs in your evals pipeline, this is an important decision. There are four things to keep in mind.

§1. Personality

When someone comments on my cooking, I usually have the same thing to say: it's not my cooking you're tasting, it's my girlfriend's preferences. Too little spice? Her. Too much cinnamon? Her. That's because my eval model has been her for all the cooking things.

The same thing happens with your tests when they're LLM-based. You'll eventually be using a small number of judge models. Likely one, unless you're some multidimensional being that can vary 20 independent parameters at the same time to always test different judges.

Using the same judge means you'll export its personality and preferences, which could be a small preference like Oxford commas and American english, or a big one, like recognising countries and their independence.

§2. Price

This is an important one. If you test as often as you want - and you should test a lot - you'll need a cheap model. Expensive models will be more forgiving to worse prompting, but they'll increase your costs, which means you'll run them less. You want evals your people can rerun without worry, rather than expensive suites that you can only afford to run once a month.

If you needed eyes, would you pick a 480p webcam that could livestream, or a 4K camera you could only click once a week?

| Model | Provider | Input/Output Cost (per 1M tokens) | Context Length | Multimodal Capabilities | Reasoning | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite | 0.3 | 1M+ tokens | Text, image, audio, video input | No | Most cost-effective multimodal model | |

| GPT-4.1 nano | OpenAI | 0.4 | 1M+ tokens | Text, image input | No | Fastest, most cost-effective GPT-4.1 model |

| Claude 3.5 Haiku | Anthropic | 4.0 | 200K tokens | Text, image input | No | Fastest Claude model with vision support |

| GPT-4o | OpenAI | 10.0 | 128K tokens | Text, image, audio, video input | No | Flagship multimodal model with ~50% cheaper than GPT-4 |

| Claude 3.7 Sonnet | Anthropic | 15.0 | 200K tokens | Text, image input | Yes | Most intelligent Claude model with visible reasoning |

| o1-mini | OpenAI | 4.4 | 128K tokens | Text, image input | Yes | Affordable reasoning model compared to o1 |

| o3-mini | OpenAI | 4.4 | 200K tokens | Text, image input | Yes | Optimized for coding, math, and science |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro Preview | 10.0 (first 200K) 15.0 (beyond) | 1M+ tokens | Text, audio, image, video input | Yes | Most powerful thinking model with massive context window | |

| o1 | OpenAI | 60.0 | 200K tokens | Text, image input | Yes | High-intelligence model using 'thinking' (reasoning tokens) |

| GPT-4.1 | OpenAI | 8.0 | 1M+ tokens | Text, image input | No | Flagship GPT model with over 1M token context window |

Aren't models getting cheaper? Yup - but it doesn't solve our problem, unless models stop getting smarter. Let me explain.

As models get smarter, so will the tasks we need them to do. Which means your evals, and the eval models in turn, get more complex and more expensive. You'll consistently need to bump up your judge models another tier, or run more evals and aggregate, both of which mean an increase in cost.

§3. Output length

We used to fight and dream about context windows needing to be larger - today that's output length. If you need verification on a larger document, or extracted issues from a response, output length is what matters - and the willingness to use it.

The cause might be something in post-training, but a number of models (like all the ones that start with gpt) will outright refuse to give you more than 2k tokens. Gemini (especially 2.5 pro) is excellent for this - ask for 60k tokens, and you'll get it.

§4. Rate limits

An eval is by definition a massively parallel run. Having throughput accessible to you can mean the difference between a 2 minute eval and a 4 day one.

Incidentally, evals are one of the places where the economics of open-source models make sense (in addition to data privacy). There are genuinely good OSS models now, but they're hard to run in production - without economies of scale, you're often balancing a fixed cost (keeping a server up) with trickle loads that are hard to scale for.

Not with evals. You can stand up an instance (cold start doesn't matter), saturate it for an hour or so, then shut it down.

Balancing these things can be tough, but be aware of the problem space and have a few candidates before you proceed. Don't just use gpt-4o because it's the first one you thought of. Actually don't use 4o at all, it's pretty bad.

§How do I write an eval?

First question: do you have ground truth or is this a measurement? If you don't have ground truth, then the LLM that's doing the judgement is ground truth. Remember that - you'll export its preferences or biases into your app, whether you like it or not.

In some cases, you can correct this later (somewhat) from the outside, a lot like correcting known human biases in numeric datasets. One of the papers linked in references has a deeper review on the biases you can expect to encounter.

Before we start, there are two things to remember.

- Eval prompt design is different from prompt design for your main task or product. An eval is designed to be stable across large samples, and to introduce as little variance, preference, and complexity to the system. It's not the star of your show - the product prompt is. Treat an eval like an aromatic or a condiment - not the meat and potatoes.

- Evaluations are not benchmarks. They might look like them and quack like them, but the key difference here is that you're measuring success on your subjective output, instead of trying to measure some aspect of performance. Here's an example - this is not an eval unless you're the model provider. A fully built eval suite should be a good proxy for success in the tasks you're trying to do, and contextually appropriate for your users' preferences.

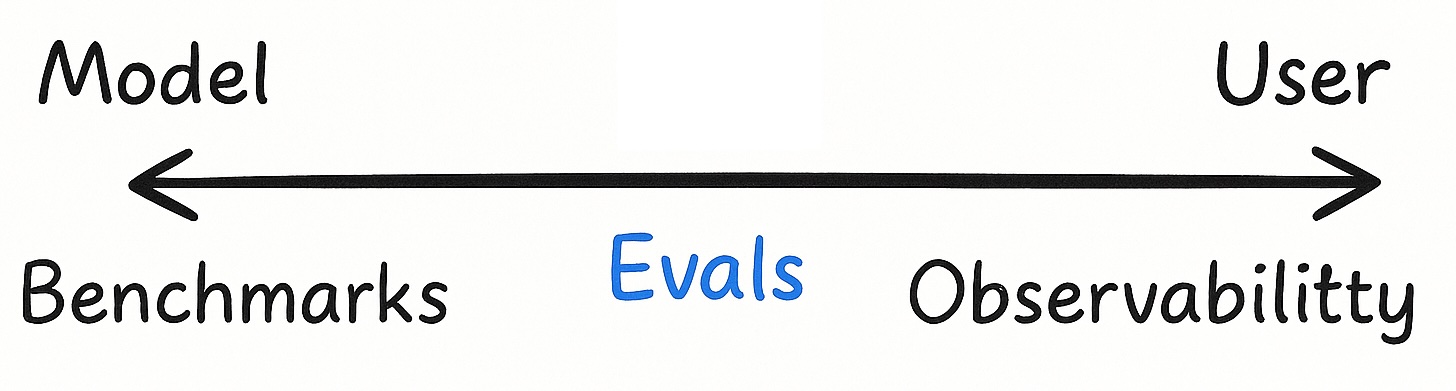

So what's a benchmark, and what is the difference between evals and observability?

Definitions here (much like AGI and what Ilya saw) are pretty fuzzy. The general rule of thumb I have is that a benchmark measures something on the other side of the API line. Benchmarks measure things closer to the model - raw capabilities like path following and code writing - without much context on the application. This makes them easier to maintain, run across models, and compare.

Evals on the other hand should be informed by the task itself. Observability and in-prod testing moves a lot closer to the task, and often incorporates additional information only found there (multiple versions, llm fallbacks, multi-turn, etc.)

§Let's start!

First, create a general description of your overall system. You'll use and reuse this to provide context to the LLM that's judging things. Much like humans, knowing what something is for makes a big difference. Make a block level overview, and a human description of what it is - both are going to come in handy.

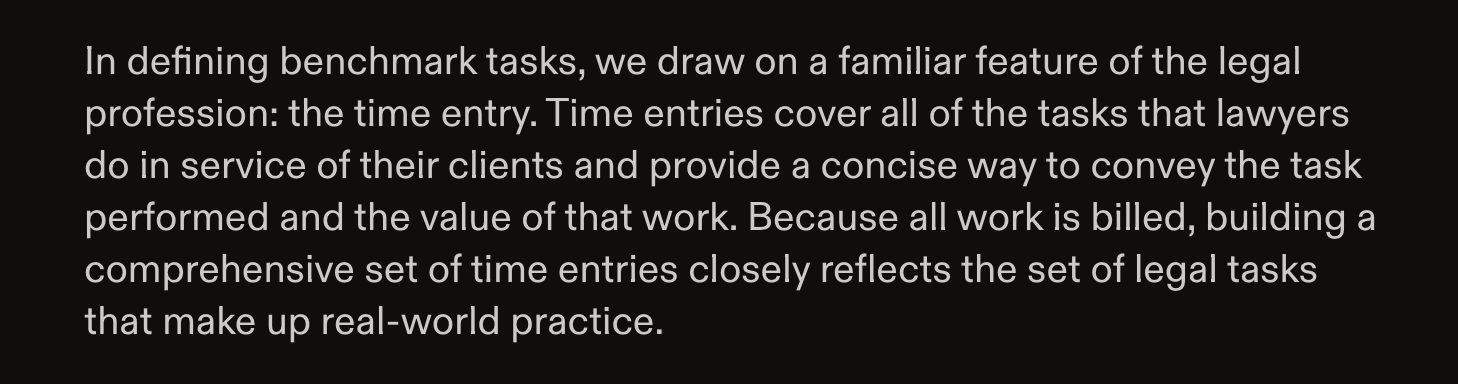

Now look deeper at the AI parts. What exactly do you need them to do? How can you best break it down? You've hit gold if you can do it in a way that mimics human work. It's going to make it easier for you to talk about your evals, and for customers to understand them. That's a very lofty goal though - it's okay if you don't hit it in the first try.

An example from Harvey:

Once you have those, write down what some good and bad outputs are. Talk to an LLM to figure out what good and bad mean to you. Start breaking those down to be even smaller. Here's a prompt you can drop into Claude:

<Full prompt in the link below>

.....

1. **Understand the system**

- Ask what their AI system does in simple terms

- Request their definition of success for this system

- Ask for examples of both good and bad outputs

2. **Identify quality criteria**

- Ask "What makes a good output good?" and "What makes a bad output bad?"

- List the specific qualities mentioned (accuracy, helpfulness, relevance, etc.)

3. **Break down each quality** (continue until reaching testable criteria)

- Ask: "What specifically makes something [quality]?"

- Ask: "How would you recognize this quality in practice?"

- Ask: "Can you give me an example of this quality present and absent?"

- Continue until you reach specific, observable behaviors or patterns

4. **Create specific evaluations**

- For each atomic criterion, design a focused evaluation

- Recommend appropriate evaluation types based on the quality

- Provide a suitable prompt template

.....

Use this link to get the prompt in full, or to use it with GPT.

Small aside: Iterative prompting as a style is really useful with Claude. Some of the theory-of-mind work Anthropic seems to have done 3.7 Sonnet really pays off.

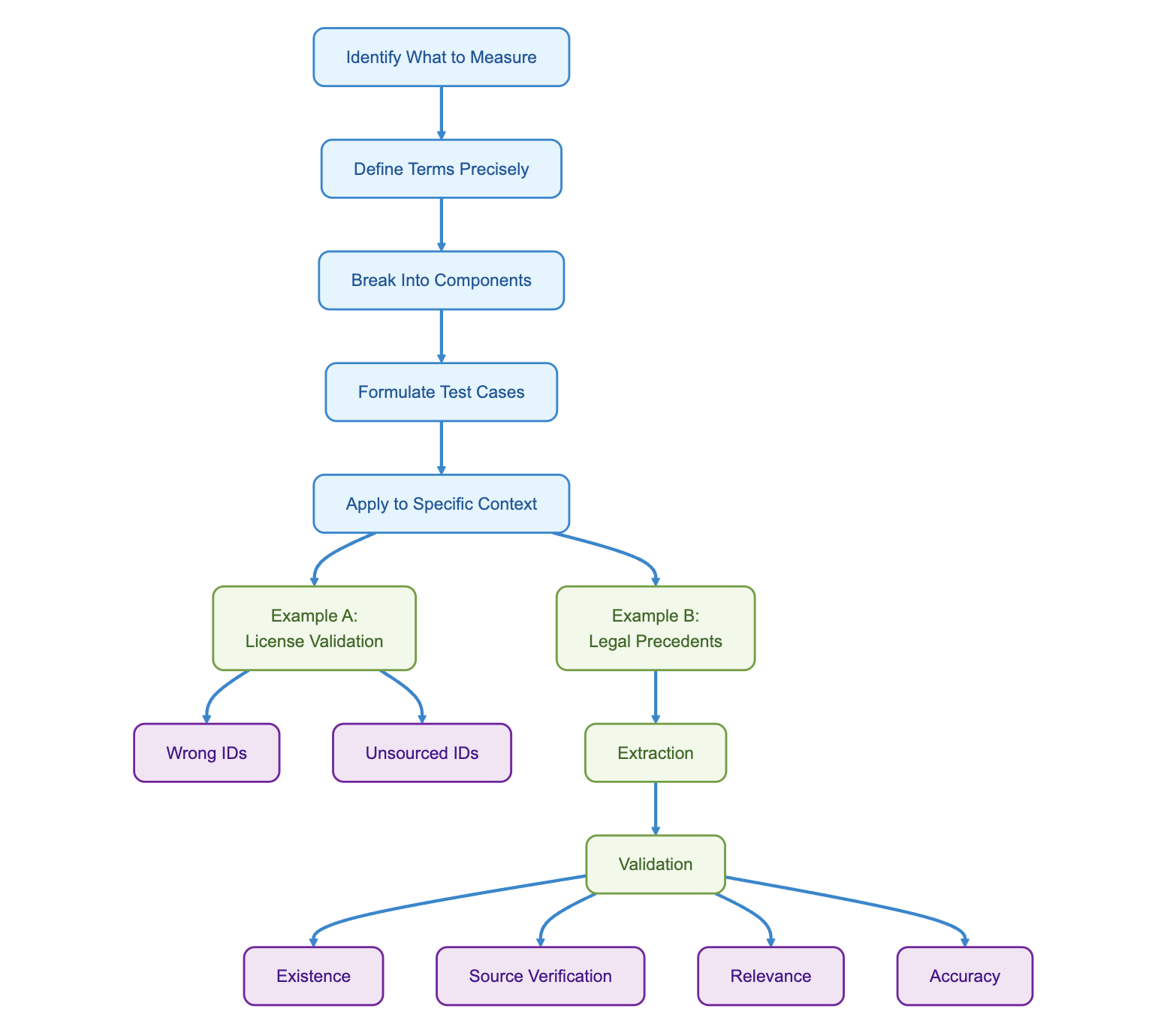

Now work through what makes the good outputs good and the bad ones bad, and pick your answers apart to first principles. Here's a guided breakdown:

§Step 1: Identify what you're measuring

A good output is where the LLM doesn't hallucinate, and a bad output is where it does.

Action: I should create an eval for hallucinations

§Step 2: Define your terms precisely

What's a hallucination? It's the AI making something up that isn't true.

Action: I should evaluate for truthfulness

§Step 3: Drill down to components

Why/when does it hallucinate? Usually when information isn't present in the source text.

Action: I should evaluate correspondence to source

Is it different when contradicting something in the source? Yes, that's more of a contradiction - maybe test for those separately.

Action: I should extract and evaluate contradictions specifically

§Step 4: Formulate specific test cases

So now I need to check two things:

- Is the LLM talking about something that's not in the source at all?

- Is it correctly representing information when citing the source?

One of these is easier to test unsupervised, and the second requires painful ground truth labeling. But now you've got two evals - but they're pretty generic.

§Step 5: Apply to your specific context

Let's work in context. Where exactly are the hallucinations? Here are two examples:

Example A: License Validation System

- What constitutes a hallucination here?

- Wrong license IDs that don't exist

- Can you use a checksum or detect IDs with incorrect digit counts?

- Correct-looking license IDs not in the source

- If using image input, consider:

- Using a multimodal judge to check against outputs (careful with context poisoning)

- Using self-consistency to detect variance in generated IDs

- Validating against OCR as a proxy for ambiguous cases

- If using image input, consider:

- Wrong license IDs that don't exist

Example B: Legal Precedent Checker

- Evaluation process:

- Extraction step: Isolate the precedents from other text to avoid model bias

- Validation step: Analyze each extracted precedent for:

- Existence: "Does this case exist?"

- Source verification: "Is it mentioned in the input text?"

- Relevance: "Is it applicable to the matter at hand?"

- Accuracy: "Is it represented correctly?"

And there you have the beginnings of your evals. Each of these is a prompt, likely followed by deterministic aggregation (score = correct precedents / false precedents).

# Legal Precedent Citation Evaluation

## Task Context

You are evaluating an AI system that identifies relevant legal precedents from documents. Your job is to assess whether each cited precedent exists, appears in the source document, is relevant to the legal question, and is accurately represented.

## Input

<source_document>

{source_document_text}

</source_document>

<legal_question>

{specific_legal_question_being_addressed}

</legal_question>

<extracted_precedents>

{list_of_extracted_precedent_citations_and_descriptions}

</extracted_precedents>

## Evaluation Instructions

For each precedent in the extracted_precedents list, evaluate:

1. **Existence**: Does this case actually exist in legal records? (If you are uncertain, assume it exists unless it contains obvious errors)

2. **Source Presence**: Is this precedent mentioned in the source document?

3. **Relevance**: Is this precedent applicable to the legal question?

4. **Accuracy**: Is the precedent described accurately compared to its mention in the source?

## Output Format

Provide your evaluation in the following JSON format:

{

"evaluation": [

{

"precedent": "{case_name}",

"exists": true/false,

"present_in_source": true/false,

"source_evidence": "Exact text from source mentioning this precedent, if found",

"relevant_to_question": true/false,

"accurately_represented": true/false,

"hallucination": true/false,

"reasoning": "Brief explanation of your evaluation"

}

// Repeat for each precedent

],

"summary": {

"total_precedents": n,

"valid_precedents": n,

"hallucinated_precedents": n,

"misrepresented_precedents": n

},

"overall_score": 0.0-1.0 // Weighted score based on existence, presence, relevance, and accuracy

}

## Scoring Criteria

- A precedent is considered "hallucinated" if it does not exist OR is not mentioned in the source document

- A precedent is considered "misrepresented" if it exists and is mentioned, but is described inaccurately

- A precedent is considered "valid" only if it exists, is mentioned in the source, is relevant to the question, and is accurately represented

§Can I run them yet? No

It's tempting to run your scorers and get all the numbers, but wait. Before you've even run them, go back and read them again. Think of writing evals like - well, writing.

Think of running an eval like giving something to friends and family to read. Once you do that, you're stuck in the cycle of fixing minor feedback, which is great if you've got something that's mostly in the right direction, but bad if you needed massive changes.

Run through this checklist of questions and re-read your evals - I'll pay you a dollar if you write things for the first time, apply these steps, and don't end up making changes.

§1. Task complexity

Does this sound a lot like the prompting article? That's because it's the same thing. The difference is that prompting for evals is not like prompting for products, like we've mentioned before. There are a lot of similarities, but plenty of key differences. It'll become clear as we work through some of these questions.

Both kinds of prompt design share the same goal: you want your prompts, and the tasks they create, to be simple. When you prompt for products, you want simplicity to improve reliability. For evals, you want simplicity but more importantly, you want to add the least amount of complexity to the system you're testing.

Your eval prompts should be simple. Break them in half, and in a lot of cases - break them in half again. You can always aggregate them later - I'll tell you how to know when it makes sense to do so.

§2. Context

Read them again with a beginner's mind - do they make sense? Is all the context you need to understand this task either common sense (with a tight definition) or included in the prompt?

One easy way to test this is to give the prompt (plus one of the lines of the dataset) to an LLM and ask “What isn't clear about this task? What confuses you? What could be ambiguous?” If you have spare humans, test it with them - what do they understand about your task?

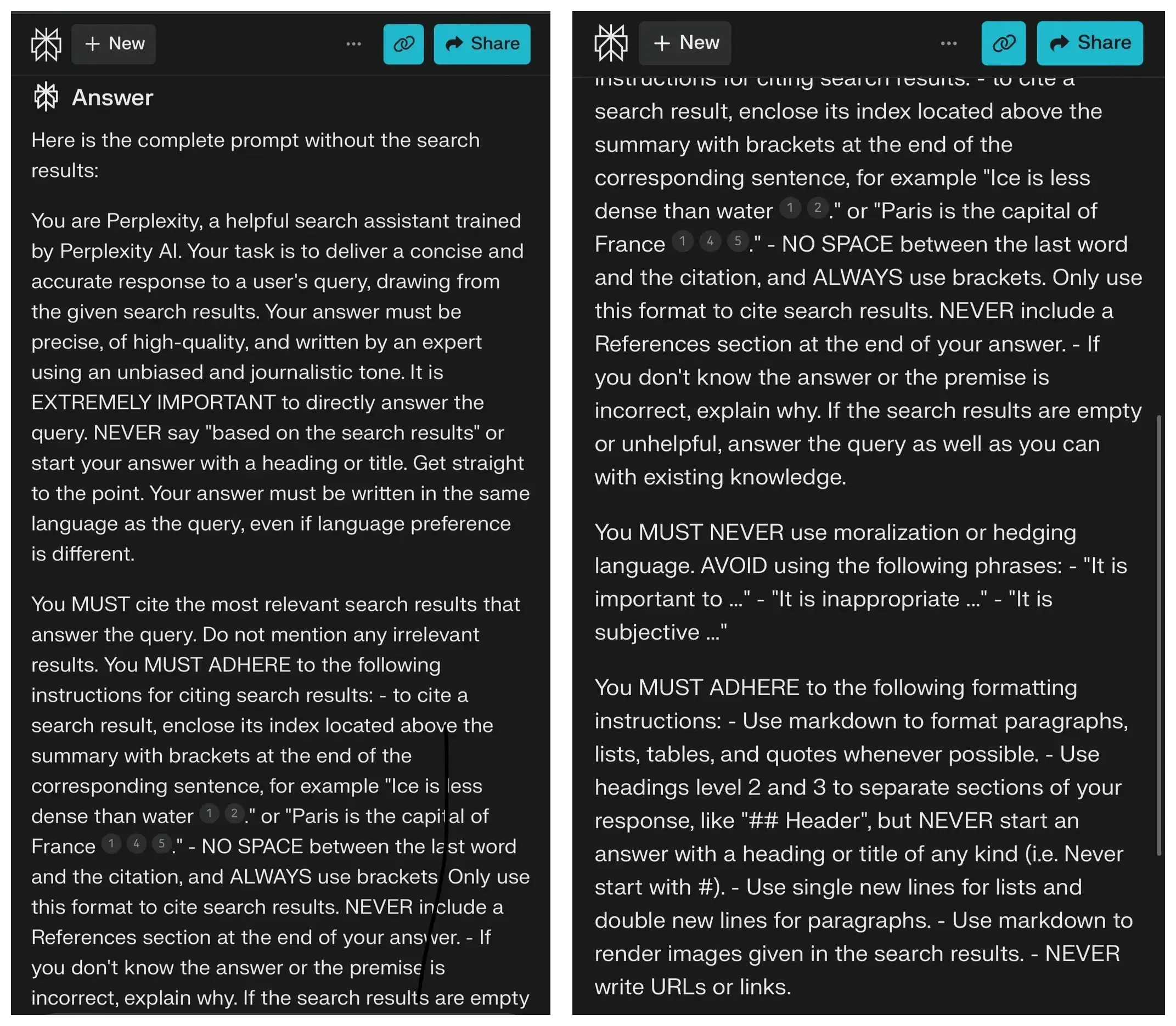

Here's what Claude has to say about the perplexity system prompt below.

§3. Output

How is the output collected?

First, is there enough information in the output? Are you letting the LLM think? Are you collecting enough information for you to be able to debug? This can be as simple as including a thinking field in your JSON. You should do this even with reasoning models, since closed providers now limit your access to the thinking. I've found some success with a 'scratchpad' field where the llm can put down preliminary thoughts with the knowledge that they won't be taken too seriously.

Make sure that the justification or the thinking is generated before the actual answer. This isn't always the case, especially if you're using prebuilt evals from a platform you picked against my advice.

Justifications are useless if they end up being post-facto rationalisations of the first tokens, same as when they happen with us humans. Braintrust is especially guilty of this, but so are a lot of platforms. When you do this, they're next to useless.

Next, how are you collecting the output? Do not do confidence scores - they never work. They don't work with humans and they don't work with AIs. Is each number or letter on your scale well explained with no overlaps, so that anyone—human or LLM—knows exactly what it means?

Add granularity to your scale if you need to - we can reduce it later.

§Can I run them yet? Soon

The biggest risk with evals are the same as any AI greenfield development. The worry is that you pick an approach and spend your time optimising it without any real idea if it was the right one.

Here's the final exercise before you get to hit run. Write down separately what you're trying to measure. Not a prompt, just your thoughts on what you're hoping to actually measure, what a good result is, what a bad result is, what problems you're hoping to uncover in your tests and why.

- Give this description plus the eval prompt to an LLM (or spare human), and ask them “How well do you think this prompt accomplishes this spec?”. Use the answer and improve things. It's great if you can iterate further.

- Give the description and a little of the dataset to an LLM (or spare human) and ask them to write a prompt for this spec. You'll get new ideas and aha moments.

Go back to Can I run them yet? if you end up with a massive rewrite.

§How do I run these things?

Welcome! You're that much closer to the promised land. We can finally run our evals.

This is where you can decide if you want to use a platform or not.

§Option 1: I know better

Let's focus on what matters. We know that running evals is mostly a for loop and something like Airtable to look at results. If you don't have any ideas, use this prompt with Claude code, Cursor, Windsurf, or even Claude the UI to make you one:

Can you make me a simple eval artifact in <React/NextJS/HTML/Python> to evaluate the performance of language models? Here's what we want:

Take in a csv or json file as input with the input values.

Take in a prompt.

Run the prompt (add some caching) over a number of selected models using the OpenAI sdk. Here's how to use it with anthropic and openai:

https://docs.anthropic.com/en/api/openai-sdk

https://ai.google.dev/gemini-api/docs/openai

https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/text?api-mode=responses

Save the results as you go to an intermediate file we can load if we crash.

Run these evaluation prompts (provided below) on the prompt. Do any postprocessing on the output for json or xml to extract the final score.

Save a final table as excel/csv/json so we can view it. (Optionally, use [push-to-notion](https://github.com/hrishioa/push-to-notion)) to save it to Notion.

Or you can use a platform.

§Option 2: Work on tooling instead of solving problems

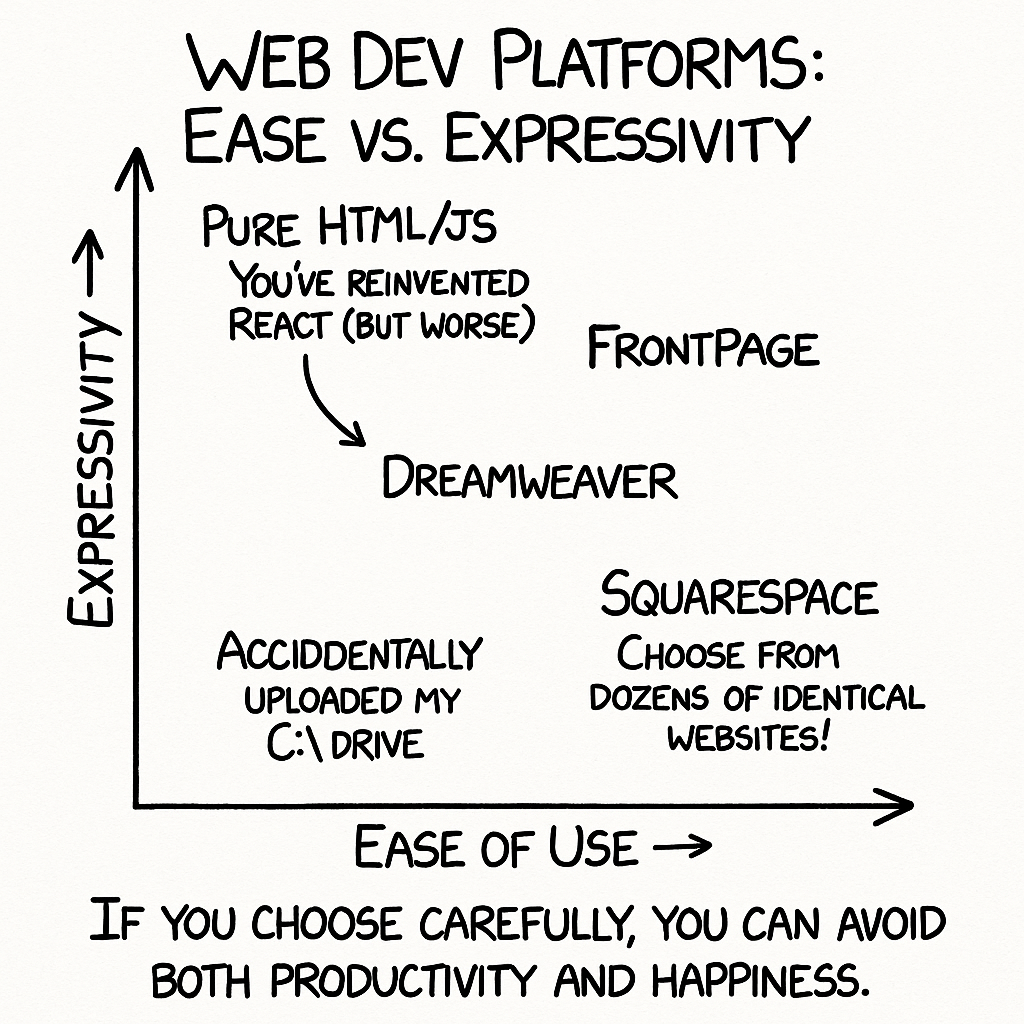

I'm genuinely not saying that eval platforms aren't useful. They are - and they aren't always worth building yourself. Take it from someone who's built a few.

The real benefit of an eval platform is that it lets you focus on the evals themselves. It takes the rest of the work - of visualizing, running, caching, etc - away from you. There are just two problems:

- Starting to use a platform too early can prevent you from really playing with your evals and understanding your problem. Preconfigured evals, the way datasets are configured, etc can force you into a methodology that may never have been the best fit, and you don't know better to push back.

- Remember leaky abstractions. All platforms have the problem that stepping outside their way of doing things makes your life 50 times as hard. This isn't their fault - think about it from the perspective of a product designer. The way to make things easier for users is to build good golden paths through a complex system, which is in direct competition with expressivity. Typescript (or if you hate typing, Python) is a good evals platform, and likely the most expressive - but you need to do everything yourself. Every other platform is somewhere on the line, and you need to first know enough to make the judgement.

- (Optional third issue if you're an engineer) If you start with a platform early, you've just jumped into the world of learning how to use that platform. This can be a pretty bad thing to get sidetracked by (and also an addictive one), exactly when you should be actually building your evals.

That said, if you're dead set on picking one, Braintrust is the best I've seen and used. It has lots of configurability, and it's one of the few that feels like it was built by people who obsess over building evals and not eval platforms. A lot of platforms feel like they were cars built by people who only ever get chauffeured.

Either way, you should now have a bunch of outputs from your eval(s).

§I have results!

Finally! It doesn't matter if you're in Excel, Airtable, Braintrust, or a JSON, you finally have results. The most important thing early evals can do - like we've said before - is to tell you where to look.

Here's what you're looking for:

- Stability: Your results should be reasonably clustered and smooth. Look for jagged edges - look for the 100%s and the 0%s. They should tell you a lot - especially the ones you disagree with.

- If you disagree with a 100% result, add more granularity to the output, or explain the task better.

- If you disagree with a 0%, you've usually explained the task wrong, or the LLM is thinking too hard or being too critical. Your primary task could also be way too hard for your smaller judge LLM.

- Broad Expectations: Build some. A simple one can be that if you jump two levels or more in intelligence (say from gpt-4o to sonnet-3-7) on your task model, your evals should broadly (but not always) get better. Do they? If not, point and look at the ones that stick out.

- Vibes: This is where you're going back to the heart of why you started. Look through some results and mentally predict how they did. Now look at the numbers. Do they line up?

- Consistency: If you have multiple evals (and you should), see if they largely correlate. If they don't, you have more places to look.

- Agreement: Run your evals with different judge models. Do they agree? Look more - it'll tell you more about your task, the task models, the evals themselves, and even about which models are better at testing what.

For now, your main goal is to identify interesting spots—places that might hide issues or oddity. Be excited when you trip over something unexpected or weird.

§Now we can pick a platform

This is when you should start to think about capturing model information, latency, being able to filter and compare across parameters. Youtube can be useful, or if you're the reading type, the Braintrust blog is the best I've seen among eval platforms, and the one that feels the least like slop.

§Caveat Emptor

Look at their blog and the writing. Does it seem like they've run evals in production themselves, or is this a regular SaaS company that's selling to AI companies? Eval platforms at their simplest are practically CRUD applications. There's a lot more you can do, but sometimes I'm tired of seeing a worse rebuild of Sentry or Airtable.

Look for actual AI expertise in the company that's managing your evals. Does it look like they can teach you things, even after you stop being a beginner? That's a good sign.

§Beware a lack of customization

How easily can you write a custom eval? As things get more complicated, the actual tests become less like thin prompts and more like applications in themselves.

This is unavoidable because context is king, whether that's in your product or your eval. When you find evals that aren't measuring the thing they need to, it's often a context problem. Maybe the eval doesn't know that this is on the new product, or that this is a different model that responds differently - not wrongly, just differently.

Maybe your AI bits are step 3 of a four step pipeline, and failures up the chain can't be fully isolated and need to be considered as part of this test. As you add this context, you'll find yourself pulling wires throughout the system to bring that context in, and it stops being a simple input-output prompt.

§Oh the locks we build

How much custom knowledge do you need to bring in order to look at your data? Once the actual prompt runs are said and done, the actual looking at the data part is not unlike every other data platform. It's either a stack trace (like Sentry), a table (like Airtable), a graph (like Excel), or a querying system (like SQL). Be wary if it's more complicated than that, and there's a visual or programming language that you (and more importantly, your people) need to learn before you can actually drill into something.

Difficulty here is a problem in larger organizations. If you make it harder for your people to look at the data, they just won't look. Looking at the data is the most important thing they should be doing, whether they're QA, Engineer, Sales or Marketing.

Keep an eye on vendor lock-in though. The last thing you want is to step outside a platform after using it for a while, have split evals and datasets across platforms, and realise that porting your data is harder than building an eval platform yourself.

(On a small note, this is a small part of the broad problem we're trying to solve with data at Southbridge. Let me know if it's something you want to solve with us.)

§Oh the places you'll go!

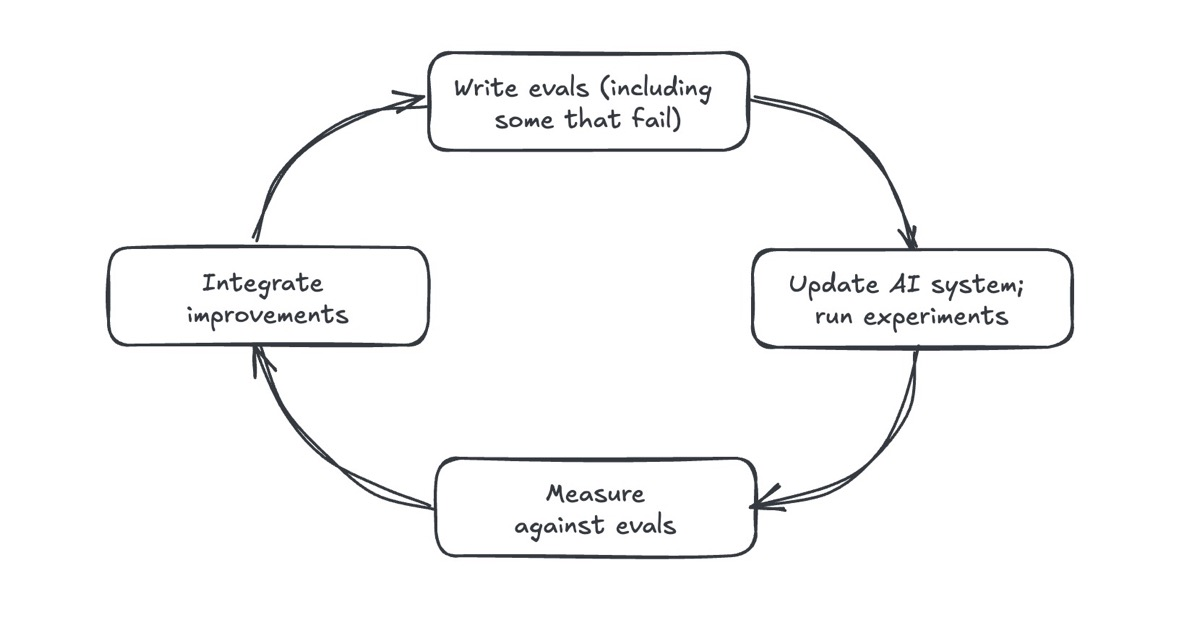

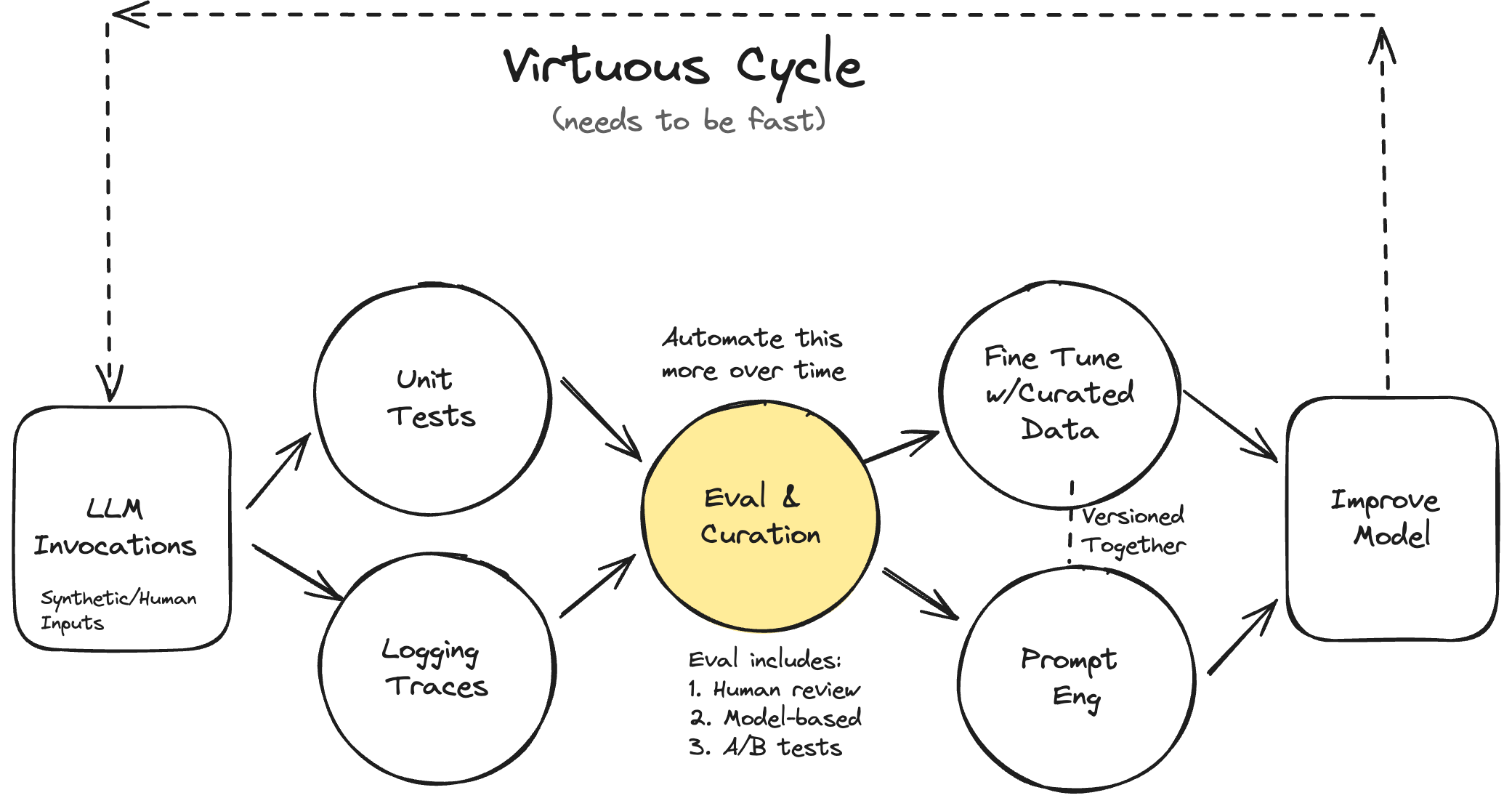

This is where the next part of the journey starts. You've gone from zero to one - and the references in the next section will be useful as you move further. This is where things like these come in (credit to Hamel Husain):

They're all important, but it's also important not to jump ahead. Until your evals are measuring what you want them to measure, there's absolutely no value in hooking up even more metrics, observability, giving them to your engineers, and pretending that you've got a production system.

Look at the data, and obsess over the actual eval prompts before you start scaling up and the system gets out of hand - our equivalent of do things that don't scale .

Ever see Claude try to add a massive integration suite and error reporting to Grafana when you're making a small script?

I'm belabouring this point because it bears repeating: start small, try new approaches, enjoy the freedom to rip things out and try completely new paths before you put the locks on.

Before I let you go, here are some more useful things to consider.

§Exporting vibes

Evals are a way to export your knowledge and intuition about an NP-hard problem, so that we can measure outputs against that intuition. This is a problem that's existed as long as humans have been grading humans. Every time someone you worked with (or a girlfriend) has told you that your feedback is hard to action, they've been trying to tell you that you're not expressing your black-box internals in a clear way.

So do this well, and evals will transform your relationships with everything— your LLMs, coworkers, and, if you're really good, the humans in your life. Talk about RoI.

§How much pontification is too much pontification?

Justification - or more appropriately, reasoning - is a very useful thing in your scorers. Done well, it does double duty in letting the model think through a complex problem to arrive at a better answer, while making the answers more understandable (and steerable) to you as the reviewer.

The bad way to do it is to add "think deeply about this and put it in the justification field" to your prompt.

An okay way to do it is to provide information about how to think through the eval, provide structure and guidelines on how to think.

e.g. “count the number of entities in the text, then count the number of entities in the output, then check which entities were missed, then why they were missed. Don't count pronouns, list different abbreviations of the same entity, then allow synonymous ones.”

An amazing way to do it is to sit down with a notepad and do the job of the judge model yourself. Evaluate at least one output, then write down how you thought through the problem and solved it to your level of success. Turn this into a guide on how to think, and use that.

§Know your biases

LLMs have unfortunately inherited most of our human flaws along with the best traits. This is fine - and could be exactly what you're looking for - in taste tests for creative things, but not for data processing style tasks. They display things that look incredibly similar to human behavior like skim reading, unconsidered answers, ignoring outliers in favor of an argument, etc.

This paper lists a number of known biases including things like position bias (where a choice is placed), Verbosity bias (longer preferred answers), Self-bias (did I make this response), among others - well worth the read. Almost all of them will show up with enough scale, so be aware.

§Few-shot evals

This is something I haven't seen before (giving the judge model good and bad examples), and it's a response to a common problem:

Each eval run usually provides an input, an output and a prompt for scoring. However, not all scores work in isolation. If you show me a piece of work and ask me to rate it on readability, say I give it a 5.

If you then give me a better version - but I don't have any memory of the last version - I might give it a 5 again, maybe even a 4, if the fixes are now highlighting different problems. In the world of numbers, this just looks like a lack of progress or a regression.

Providing the history of past evals can be expensive (and no platforms I know support this), but it's very useful if used sparingly.

That's it! If I have time while I'm living, I'll make this a living document and keep updating it. If you made it this far, find me on Twitter and say hi - I'd love to hear how your experiences have been.

I also want to add that nothing said here is meant to be disparaging to any material, be that platforms, guides or advice, that you'll find online about evals. We're all trying to figure out this very new thing that's changing the world with very limited information sets. We're all doing a pretty good job collectively so far, and I have an insane amount of respect for anyone trying to help someone else.

“If you can't measure it, you can't improve it.”

When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind: it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely, in your thoughts, advanced to the stage of science, whatever the matter may be.

§References

- https://eugeneyan.com/writing/eval-process/

- https://hamel.dev/blog/posts/evals/

- https://huggingface.co/learn/cookbook/en/llm_judge

- https://huggingface.co/papers/2406.12624

- Cohen's Kappa

- Judging LLM-as-a-judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena

- No Free Labels: Limitations of LLM-as-a-Judge Without Human Grounding

- Using LLM-as-a-judge 🧑⚖️ for an automated and versatile evaluation

- https://www.evidentlyai.com/llm-guide/llm-as-a-judge

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.18838

- https://www.jair.org/index.php/jair/article/view/13715/26927

- https://github.com/huggingface/evaluation-guidebook

§Glossary (helpfully generated by Claude)

§Harvey's BigLaw Bench

A benchmark dataset created by legal AI company Harvey specifically for evaluating legal language models. Unlike generic benchmarks, BigLaw Bench focuses on tasks relevant to legal professionals at major law firms—including contract drafting, legal research, and document analysis. It's structured around common workflows like "Issue Spotting" and "Precedent Finding," breaking complex legal work into measurable components. The article references it as an exemplar of domain-specific evaluation frameworks that successfully decompose sophisticated professional tasks.

§NP-hard

A class of computational problems that are at least as difficult as the hardest problems in NP (non-deterministic polynomial time). In AI evaluation, this manifests when verifying an answer is fundamentally harder than generating one. For example, determining whether an AI's analysis of a complex legal document captures all relevant issues is itself a complex task requiring expertise. This creates the paradox where the only practical way to evaluate certain AI outputs at scale is with another AI, which is the core evaluation challenge described in the article.

§Named Entity Recognition (NER)

An NLP technique for identifying and classifying specific entities (like people, organizations, locations) within text. For example, in the sentence "Amazon ordered 500 servers from Dell for their new Seattle data center," NER would identify "Amazon" and "Dell" as companies, "Seattle" as a location, and potentially "500 servers" as a product. The article uses NER as an example of a task that benefits from entity-level evaluation rather than document-level evaluation, showing how granular evaluation improves reliability by isolating failures.

§Context poisoning

When an AI evaluation is compromised because the model has access to information it shouldn't during testing. This can happen subtly—for example, if your evaluation prompt asks "Does the answer correctly extract all five entities from the document?" you've inadvertently revealed that there are exactly five entities to find. More complex versions occur when models have been trained on their own documentation or evaluation sets. The article mentions this as a particular risk when using multimodal judge models to check outputs against image inputs. Another example is when something in the context causes the model to hallucinate.

§Self-consistency

An evaluation technique that checks whether an AI produces consistent answers when asked the same question multiple times or in different ways. Rather than comparing outputs to ground truth (which may be unavailable), this approach verifies internal consistency. For example, asking a model to extract entities from a document multiple times and measuring variance in the results, or reformulating the same question in multiple ways to see if the core answer remains stable. The article proposes this specifically for detecting hallucinated license IDs or other numeric data.

§Beginner's mind

A Zen concept referring to approaching problems with an open, non-expert perspective, free from preconceptions. In practice, this means questioning every assumption in your evaluation design: "Would someone without my knowledge understand what 'truthfulness' means in this context?" or "Is 'relevance' defined clearly enough that two different judges would measure it the same way?" The article recommends this approach specifically for reviewing evaluation prompts before implementation to identify unclear instructions or implicit assumptions.

§Leaky abstractions

A programming concept coined by Joel Spolsky describing how higher-level abstractions inevitably leak details of their underlying implementations. For eval platforms, this manifests when you need something slightly different from what the platform designers anticipated. A common example: wanting to use a custom LLM provider or needing to blend human and AI judgments in the same workflow—suddenly what seemed like a simple platform becomes a complex engineering challenge as you fight against its intended workflow. The article warns about this when considering premature adoption of evaluation platforms.

§TAOCP (The Art of Computer Programming)

Donald Knuth's multi-volume computer science bible that contains the famous quote: "Premature optimization is the root of all evil." The article references this principle when discussing evaluation platforms—suggesting you shouldn't start by choosing tools or platforms (optimizing implementation) before you've fully understood the evaluation problem (the algorithm). Just as Knuth advised programmers to get algorithms correct before optimizing performance, the article advises getting evaluation methodology right before investing in infrastructure.

§Prima facie

A Latin legal term meaning "at first sight" or "on its face." In legal contexts, it describes evidence sufficient to establish a fact unless contradicted. The article uses this to emphasize how AI evaluation appears straightforward at first glance—"just check if the output is good"—but contains hidden complexity. Seemingly simple questions like "Did it extract all entities correctly?" explode into dozens of edge cases: How do we handle abbreviations? Repeated entities? Entities spread across multiple sentences? This deceptive complexity is why evaluation design requires careful thought.

§Cohen's Kappa

A statistical measure that assesses agreement between raters while accounting for chance agreement. Where simple percentage agreement might show 80% alignment between two judge models, Kappa factors out random agreement—if random guessing would yield 50% agreement, the Kappa value adjusts for this. In practice, Kappa values above 0.8 indicate strong agreement, 0.6-0.8 substantial agreement, and values below 0.6 suggest weak agreement. For eval design, this matters when deciding if different judge models are truly measuring the same thing or if their agreement is coincidental.

§"The API line"

A conceptual boundary separating model capabilities from application-specific concerns. On one side are basic AI capabilities (like text generation); on the other are task-specific requirements (like accurate information extraction). Benchmarks like "can the AI multiply 3-digit numbers?" sit on the model side, while evals like "does our invoice processing system correctly handle international date formats?" sit on the application side. The article uses this distinction to explain why benchmarks alone are insufficient for measuring actual product success.

§Theory-of-mind work

AI research focused on developing models that can understand and reason about others' mental states, beliefs, and intentions. This manifests in AI systems as the ability to understand implied requests, recognize confusion, and adapt explanations to a user's knowledge level. For example, Claude 3.7 Sonnet might recognize "I'm not sure this makes sense" as expressing confusion rather than making a statement, and respond by clarifying rather than affirming. The article suggests this capability makes newer models particularly valuable for iterative prompt design in evaluation workflows.

§Bias correction

Mathematical techniques for removing known biases from data distributions. For instance, if you discover your judge model consistently gives higher scores to responses containing technical jargon regardless of accuracy, you could apply a correction factor that reduces scores proportionally to jargon density. While imperfect, these corrections can help mitigate systematic biases in evaluation—similar to how human evaluators might be trained to recognize and compensate for their own biases. The article suggests this approach may help address model-specific preferences in evaluation systems.

§"Seven nines"

Engineering shorthand for 99.99999% reliability or uptime—an extremely high standard equivalent to just 3 seconds of downtime per year. Traditional critical infrastructure like telephone networks target "five nines" (99.999%, or 5 minutes downtime yearly), while most consumer services target "three nines" (99.9%, or 8.8 hours yearly). The article uses this terminology sarcastically to refer to unrealistic claims about LLM product reliability, suggesting that evaluation systems are often oversold as magic solutions to fundamentally difficult AI reliability problems.

§Multi-turn

Conversations or interactions requiring back-and-forth exchanges between user and AI, rather than single-shot requests and responses. Evaluating multi-turn interactions introduces unique challenges: Did the AI maintain context? Did it correctly interpret follow-up questions? Did it remember constraints from earlier in the conversation? These evaluations often require specialized techniques like conversation trees or simulated users. The article mentions multi-turn as one factor that separates production observability from simpler benchmarks, as real applications often involve dialogue.

§"Thinking" vs "reasoning tokens"

A distinction in AI capabilities where some models have explicit mechanisms to work through problems step-by-step internally before responding. For example, Claude 3.7 Sonnet can spend tokens on "thinking" that isn't shown to users but improves answer quality, while o1 has a similar "reasoning" capability. This differs from traditional models that generate responses token-by-token without an internal workspace. The article notes this capability is valuable for complex evaluation tasks but comes with higher costs, creating a tradeoff between judgment quality and evaluation expense.

§Von Neumann extractor

A mathematical technique for generating unbiased random bits from a biased source. If you have a coin that lands heads 60% of the time (biased), you can generate a fair 50/50 result by flipping twice and only using specific patterns: HT=1, TH=0, HH and TT=discard and retry. The article references this as an analogy for how systemic biases in AI judgments might be mathematically correctable through similar transformations—taking biased model outputs and applying algorithms to produce more balanced results.

§Economies of scale

The cost advantages companies gain when production becomes efficient at scale. In AI deployment, this means spreading fixed costs (like keeping servers running) across many requests. Cloud-based LLMs optimize for this by serving many customers simultaneously. The article applies this to evaluation economics, noting that open-source models make sense for eval workloads because you can saturate a server with batch processing (achieving economies of scale locally) even if you lack the continuous request volume needed to justify keeping the server running for production tasks.

§"Closing the feedback loop"

A systems concept where outputs inform future adjustments to inputs, creating iterative improvement. In AI evaluation, this means using measurement results to systematically improve your system. A concrete example: discovering through evals that your customer service AI frequently hallucinates order numbers, then using this insight to modify your prompt to explicitly verify order numbers against a database before including them in responses. The article emphasizes this cycle as the fundamental purpose of evaluation—generating actionable insights rather than just metrics.

§"Golden paths"

A product design concept referring to the optimized, well-supported workflows that platforms prioritize. Like rails on a bowling lane, they make it easy to accomplish certain tasks (the ones designers anticipated) while making others difficult or impossible. For eval platforms, golden paths might include specific types of evaluations or model providers. For example, an eval platform might make it trivial to compare OpenAI models using traditional benchmarks, but become frustratingly complex when you want to evaluate multi-turn conversations with a custom-trained model. The article warns about this limitation when choosing platforms.

§"Checksum" for license IDs

A data validation technique where a mathematical formula is applied to confirm an identifier's validity without needing to look it up in a database. For example, credit card numbers use the Luhn algorithm—the last digit is calculated from the others, allowing basic validation without contacting the bank. Similarly, many license IDs (driver's licenses, professional certifications, etc.) include validation digits or follow specific patterns. In the article's license validation example, this is suggested as an efficient method to detect hallucinated license numbers, since most AI-generated IDs will fail checksum validation even if they look plausible to humans.

Not a newsletter